LASA hosted its first Annual Historical Dinner in Lethbridge, Alberta, at the Galt Museum and Archives on Thursday, April 13, 2023. We were delighted to welcome Dr. Adriana Davies, author and historian, who spoke about an historical case that took place in southwestern Alberta during the prohibition period after World War I.

LASA hosted its first Annual Historical Dinner in Lethbridge, Alberta, at the Galt Museum and Archives on Thursday, April 13, 2023. We were delighted to welcome Dr. Adriana Davies, author and historian, who spoke about an historical case that took place in southwestern Alberta during the prohibition period after World War I.

The speech, based on her book The Rise and Fall of Emilio Picariello, examines the conviction and execution of Emilio Picariello and Florence Lassandro for the alleged murder of Alberta Provincial Police (APP) Constable Stephen Lawson in September 1922.

Dr. Davies told the audience that she considered the story a cold case with the very real possibility that their executions were a miscarriage of justice, morally and legally.

legally.

Her speech detailed the background of Picariello’s immigration from Italy to the United States through Toronto to Fernie. To put this period of migration to western Canada into context, preferred immigrants were of British background from England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland. Immigrants from southern Europe, including Italy, were considered less desirable. According to Davies, the immigration hierarchy, in place at the time, was based on race and socio-economic status.

There was a well-established Italian community in the region by the time the Picariellos arrived in Fernie in 1911. Eighteen percent of the workforce in the Crowsnest Pass was of Italian decent. Statistics indicated that there were more Italians living in the Crowsnest Pass than in Calgary and Edmonton. Mainly toiling in labour jobs, the coal mines, and other extraction industries, which were viewed as work ideal for Italian immigrants. Emilio operated a macaroni factory, expanding into ice cream. He was also a bottle picker (how he got his nickname “Pic”) selling bottles back to the distilleries in the area.

Florence Lassandro was barely literate. Her father worked on the Kettlecreek Railway, and in various mines in the region. Being a small community that was tightly knit, the Lassandros and Picariellos were close friends. Because of the close ties between the two families, as well as Florence’s troubled marriage, historical accounts have surmised that either Emilio and Florence were having an affair or Florence was involved with Steve Picariello, Emilio’s son. Though she did live in the Alberta Hotel in Blairmore, which Emilio owned, there is no concrete evidence to suggest any affair took place.

It was because of her own immigration story – Dr. Davies was born in Italy and came to Canada in the post-World War II period – the stories of Italian immigrants in Canada, in particular the southwest region of Alberta, was intriguing. She recalled her own experiences of discrimination based on her race and heritage in 1950s Canada. But it was not until developing the Picariello profile for the “Mavericks” exhibit at the Glenbow Museum that she turned her attention to this story.

She recalled that she was initially convinced of their guilt. On the face of it, all the evidence pointed toward their guilt. However, things changed in the fall of 2015, while working on the development of a travelling exhibit for the Fernie Museum. Davies began to doubt her initial beliefs. During the research for her book, she began to question how racism and discrimination may have played a role in the criminal justice system towards Picariello and Lassandro.

All the main players in this historic episode had one thing in common, they were all immigrants. Though many were from Italy, a number, including Constable Stephen Lawson, was from the United Kingdom. But in a story about prohibition and bootlegging, the main protagonist was alcohol. The movement to ban the sale and consumption of liquor believed that the vice was inextricably linked to many societal ills, such as poverty, crime, unemployment, and family violence. For many in the Temperance movement, all of this was directly linked to race and ethnicity.

All the main players in this historic episode had one thing in common, they were all immigrants. Though many were from Italy, a number, including Constable Stephen Lawson, was from the United Kingdom. But in a story about prohibition and bootlegging, the main protagonist was alcohol. The movement to ban the sale and consumption of liquor believed that the vice was inextricably linked to many societal ills, such as poverty, crime, unemployment, and family violence. For many in the Temperance movement, all of this was directly linked to race and ethnicity.

Governments across the country, including the federal government, banned the manufacture of alcohol during the latter part of the First World War and in its immediate aftermath. As Davies argues, banning its manufacturing did not diminish the want for alcohol and led to a period of illegal production and sale. In fact, a majority of citizens in the Crowsnest Pass area voted against prohibition. The convergence of Alberta, British Columbia, and the United States, became a promising region for the bootlegging trade.

Like many businessmen in the area, Picariello became involved in bootlegging after February 1918 when he purchased the Alberta Hotel in Blairmore. He was able to sell prohibition beer in his hotel, but the real money was to be made selling illegal hard liquor. Up until the passing of prohibition laws in the United States, Picariello was getting his liquor from key sources in Montana. He was completing regular liquor runs between BC, Alberta, and Montana, known as the ”Whisky Gap”.

Davies suggests that Picariello’s bootlegging business was the worst kept secret in the Crowsnest Pass. Despite their racialized bias towards Italian immigrants, the British continued to purchase alcohol from Emilio. It was during this time that Picariello became the favourite target of APP Sergeant James O. Scott, who was very much in favour of prohibition. However, between 1921 and September 1922, policing prohibition became increasingly dubious as BC repealed its prohibition laws, meaning liquor could legally be purchased just across the provincial border.

Davies told the audience that authorities took the policing of liquor laws very seriously. The police in the region were mainly of British decent and many had previous policing or military experience. What is interesting, however, is that the major players in bootlegging also came from Britain. She suggests that the police enforcement against Italian bootleggers – who were very successful – was based on race and class attitude.

Wrapping up the background to prohibition in the region, Dr. Davies shifted focus to the shooting of Constable Lawson that resulted in Picariello’s and Lassandro’s executions. The authorities in the region received a tip that Emilio would be completing a liquor run to Fernie on September 21, 1922. The police set a trap that involved officers from Coleman, Blairmore, and Lethbridge. At that time, liquor runs were rudimentary: one car would act as a scout car that could warn the second car carrying the illicit alcohol of police roadblocks requiring a change of direction.

On that fateful afternoon, returning to Alberta from Fernie were Picariello, Jack McAlpine, and Steve Piciarello, Emilio’s sixteen-year old son. All three were driving their own McLaughlins, but it was Steve’s car that was filled with whiskey. Upon returning to the Alberta Hotel in Blairmore, Emilio was confronted by Sergeant Scott. The former was able to warn his son who then attempted to return to Fernie. It was during the subsequent car chase through the Crowsnest Pass that Constable Lawson shot several times and hit Steve in the hand. It was only because of a flat tire that the two officers were forced to abandon their pursuit. Steve Picariello was able to reach Natal, BC, relatively unscathed.

It is at this point, Davies suggests, the details differed, laying the groundwork for Constable Lawson’s shooting. According to the police, Emilio was enraged to learn that his son had been seriously hurt during the car chase back to BC. However, the records indicate that while in Natal, Steve was able to find a doctor, tend to his injury, and locate a phone to call his father letting him know that he was alright.

It is at this point, Davies suggests, the details differed, laying the groundwork for Constable Lawson’s shooting. According to the police, Emilio was enraged to learn that his son had been seriously hurt during the car chase back to BC. However, the records indicate that while in Natal, Steve was able to find a doctor, tend to his injury, and locate a phone to call his father letting him know that he was alright.

Emilio then tried to enlist the help of Constable Lawson for the safe return of Steve to Alberta. At 7 pm that evening, Picariello and Lassandro arrived at the APP detachment in Coleman at which time Constable Lawson emerged from the barracks and a confrontation occurred. While the two men were fighting it was reported that four to six shots rang out, one of which killed Constable Lawson. The two alleged perpetrators, Picariello and Lassandro, fled the scene and headed back to Blairmore where they hid within the Italian community. Both were in police custody by the end of the day on September 22, 1922.

Headlines in the wake of their arrest pointed immediately to their guilt. In fact, many newspaper reports described Picariello as some sort of criminal mastermind. Erroneously reporting that the Italian immigrant hailed from Sicily – home of the mafia – the press made the dubious connection between Italian immigrants, the mafia, and criminal behaviour. It was clear, Davies suggested, the court of public opinion had already convicted them before the trial had even begun.

The defence at the preliminary hearing was led by Lethbridge lawyer, Charles Harris, who during the course of proceedings decided to try the two accused together and offer a plea of self-defence. Harris also motioned for a change of venue to Edmonton believing his clients could not receive a fair trial anywhere in the Crowsnest Pass. Attorney General, John E. Brownlee, reluctantly agreed to a change of venue, but set the trial for Calgary.

The case of R v Emil Picariello and Florence Lassandro took place in the Calgary Court House from November 27 to December 3, 1922, only nine weeks after the shooting in Coleman. Brownlee, a staunch proponent of prohibition, laid the murder charges in court and attended every day of the trial. Mr. Justice W.L. Walsh, of the Supreme Court of Alberta, presided over the trial. The prosecution was headed by A.A. McGillivray. Picariello, unhappy with Harris, replaced him with J. McKinley Cameron to defend himself and Lassandro.

Cameron continued with the self-defence plea because he believed his clients were innocent. Davies is critical of Cameron for proceeding with this defence, arguing there was no evidence nor witnesses to support it. However, she suggested that police ignored the forensic evidence at the scene. There were pools of broken glass on the floor inside the car. This suggests that the shots came from outside the vehicle, not from inside the car as the prosecution and police claimed. Florence, who was sitting inside the car, testified that she saw two flashes from shots outside the car. Picariello always maintained that the shooter was in the alley.

With the jury finding both defendants guilty, Judge Walsh sentenced them to hang at the Fort Saskatchewan Jail on February 21, 1923. Cameron immediately set appeals in motion that eventually took the case to the Supreme Court of Canada. After all appeals for a new trial were exhausted, Cameron wrote to the Governor General in a “last-ditch” effort to ask for clemency, but that was also rejected.

An undated memo in Cameron’s files records that he called for clemency because the execution of a young woman was morally objectionable in a modern society. Believing the trial was unfair from the beginning, he maintained the accused could never have received a fair trial as they were immigrants profiting from an illegal trade that led to the killing of an APP Constable and World War I veteran. Lastly, he reasoned that the trial happened far too quickly after the murder and emotions were still high over the murder of a police officer.

An undated memo in Cameron’s files records that he called for clemency because the execution of a young woman was morally objectionable in a modern society. Believing the trial was unfair from the beginning, he maintained the accused could never have received a fair trial as they were immigrants profiting from an illegal trade that led to the killing of an APP Constable and World War I veteran. Lastly, he reasoned that the trial happened far too quickly after the murder and emotions were still high over the murder of a police officer.

Cameron was not alone in questioning the morality of executing a young woman. Although some believed that Picariello should be hanged, they cast doubts on Lassandro’s sentence. However, a majority of the public was against the defendants, including Magistrate Emily Murphy, who was a strong supporter of prohibition and a believer in the rule of law. She did not accept that clemency should be granted to a woman convicted of such a heinous crime simply because she was a woman.

Dr. Davies concluded her speech commenting on the legacy of prohibition in Alberta. She showed that the killing of Stephen Lawson and the execution of Lassandro and Picariello called Alberta’s prohibition laws into question. It had quickly become clear that criminalizing the consumption of alcohol was not without its unintended victims. In fact, the authorities began to realize this before the two were executed on May 3, 1923. In April 1923, a petition to repeal prohibition in the Crowsnest Pass region was submitted to the Alberta government. The government of Alberta then held a plebiscite in October 1923 that officially ended prohibition.

***************************************

Wait…this was not the end of the story.

During his acknowledgement of Dr. Davis, Mr. Justice Kevin Feehan of the Court of Appeal of Alberta spoke about his involvement in the Picariello and Lassandro saga.

During his acknowledgement of Dr. Davis, Mr. Justice Kevin Feehan of the Court of Appeal of Alberta spoke about his involvement in the Picariello and Lassandro saga.

It was December 19, 2017, when he was sitting as a Queen’s Bench Justice in Lethbridge and found himself with a few hours of spare time between hearings. Mr. Justice Dallas Miller drove Justice Feehan to the Galt Museum to see the traveling exhibit about Picariello and Lassandro developed and curated by the Fernie Museum and Adriana A. Davies.

He was fascinated by the story as he walked through the exhibit but was surprised when it came to the last panel, which read in part: “On May 2, 1923, Picariello and Lassandro went to the gallows at the Fort Saskatchewan Gaol…They were buried in unmarked graves, next to each other, in an Edmonton cemetery. The families were refused permission for private burials.”

This last panel surprised him, as he knew both the location of those graves and the fact that they had now been marked.

The reason, he told the audience, that he was certain of the location and that the graves had been marked was because he acted in 2010 in a complex matter of a shareholder dispute and estate litigation that arose following the death of William Connelly Sr., the proprietor of Connelly-McKinley Funeral Homes in Edmonton.

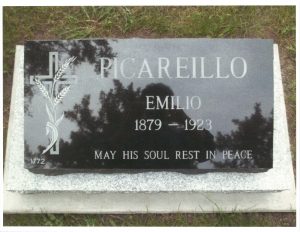

For the purposes of this “Afterword”, paragraph 4(e)(ii) of the Will states the following specific bequest: “The sum of $2,500 to provide a suitable marker for the graves of Emilio Picarrello [sic] and Florence Lesander [sic], who were executed at Fort Saskatchewan, for historical purposes.”

Attachment 1 – Will of William James Connelly

Attachment 2 – Picariello and Lassandro grave locations map

Gerry Connelly told Justice Feehan (at the time, a lawyer with Dentons in Edmonton) that his grandfather, Joseph William Connelly, had been present at the hangings of Picariello and Lassandro, and had been provided with their bodies for the purpose of internment. His instructions, at the time, were to bury them in unmarked graves, without headstones, and to keep the location of the graves secret.

It was William James Connelly who later became enamoured with the story of Picariello and Lassandro, and the circumstances surrounding the shooting of Constable Lawson, the subsequent court proceedings, and the conviction and execution. He believed that the two were wrongly convicted.

In 2011, Gerry Connelly, with a hand drawn map passed down by Joseph William Connelly to his son and then grandson, located and marked the graves of Picariello and Lassandro in the Oblate Fathers’ section of St. Joachim Cemetery for the future erection of headstones.

On December 20, 2011, Justice Feehan (still a lawyer) corresponded to legal counsel for the estate of William Connelly Sr., instructing placement of the tombstones. He concluded his “Afterword”: this now completes the final chapter in the fascinating Alberta story of our most famous prohibition rumrunners.

The Legal Archives Society of Alberta wishes to thank all those who attended this wonderful evening and who continue to support our work to preserve and promote Alberta’s legal heritage. LASA wants to thank all the organizers of the event, especially Justice Dallas K. Miller, Leslie Stitt, Nikki van Mulligen, and Kerry Gellrich, as well as the evening’s speakers who helped make this a memorable evening. We also extend our thanks to Dr. Adriana Davies, who graciously accepted our invitation.