Stacy F. Kaufeld, M.A.

Originally a speech presented to the Calgary Association of Lifelong Learners on October 7, 2025

What is Legal History

In 1973, legal scholar R.C.B. Risk published “A Prospectus for Canadian Legal History” in the Dalhousie Law Journal. Considering the absence of legal history in Canada, Risk’s argues “our understanding of history cannot be complete without some understanding of its legal elements.”[1]

Until the mid-1960s legal history was examined by Canadian historians only in the periphery. It remained almost the sole purview of legal scholars who focused on legal doctrines, traditions, biographies, and court structures, which failed to appreciate legal history within the broader Canadian experience. Since law is an integral aspect of human society, its history should be included within the wider context of Canadian political, social, and economic developments.[2] Understanding how various forces shape the law and how the law affects society has made legal history more relevant and engaging for historical research and public consumption.

John McLaren, the first Dean at the Faculty of Law at the University of Calgary, writes, “Albertans have been in the forefront in the teaching and research of Canadian legal history since the mid-1960s.”[3] But it was only in the 1970s when Louis Knafla, Professor History at the University of Calgary, met the challenge to increase awareness of Alberta’s legal history. In 1978, with the assistance of Roderick Macleod, a legal historian at the University of Alberta, Knafla established the Alberta Legal History Project with funding from the Alberta Law Foundation. The project aimed to preserve courthouse records as a valuable primary source for researchers studying the legal history of the Northwest Territories and Alberta.[4]

There are two types of records for legal history. First, official government records generated at the national, provincial, or local level that cover court administration, the judiciary, and any related governmental or ministerial departments.[5] While these records are undeniably important, they limit the scope of legal history as Risk critiqued in his “Prospectus”. Second, private sector legal records, covering documents from independent members of the legal profession, including lawyers, judges, as well as professional and services organizations detail the relationship between the legal system and the people that it serves and are not available in the official government records.[6]

Combined, these records offer historians the opportunity to analyze the nature and extent of the legal system’s influence on society.

The Early Calgary Contribution

I hope to show how the establishment of formal law in Calgary’s early years was shaped by economic, political, and social factors.

Formal law came in stages to southern Alberta, beginning in 1874 when the North West Mounted Police arrived. Between 1875 and 1885, the administration of justice for Calgary occurred from Fort Macleod where Colonel James Farquarson Macleod was headquartered.

Calgary quickly became the commercial centre of the west after the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) arrived in August 1883. Frustration set in among city leaders as business activities were disrupted because Macleod only arrived on circuit twice a year.[7] Lawyers, including James Lougheed, were deeply involved in major commercial, agriculture, and industrial activities that sometimes involved complex land transactions, partnership agreements, and company incorporation that often required the courts.[8] Without a permanent judge in Calgary, its economic growth was haphazard and slow.

Following some pressure on the Dominion government and even an attempt to petition to move Colonel Macleod permanently to Calgary – against the wishes of the residents in Fort Maclead – the government appointed Stipendiary Magistrate, Jeremiah Travis, to Calgary on July 30, 1885.

Travis’s time in Calgary was fraught with controversy. Calgary being a typical frontier town with widespread gambling, prostitution, and alcohol consumption with many of its leading citizens, including the mayor, town solicitor, and constable, either ignoring or enabling this illegal activity.[9] Travis, a teetotaler and support of prohibition, opted to confront the problem first by sentencing local hotelier and town councilor, Simon John Clarke, to six months hard labour and, second, firing his clerk of the court, Hugh Cayley, for showing up at court drunk. Though the two arrests are very much connected, it was the latter that ended up causing trouble for Travis. In addition to being clerk of the court, Cayley, who had an influential uncle in the John A. Macdonald government, was also editor of the Calgary Herald.[10]

Travis examined allegations of corruption related to inconsistencies found in the 1886 voter list ahead of the municipal election during this time. At the centre of the allegations was the incumbent Mayor, George Murdoch, who was implicated in the so-called “whiskey ring”. Travis found Murdoch and two councilors guilty of election fraud. Although barred from running and holding office for two years, their names stayed on the ballot, and they were reelected by large margins. Travis immediately rejected the results and appointed James Reilly as Mayor along with a substitute council.[11]

The chaos emerging in Calgary caught the attention of the Dominion government who asked Manitoba judge Thomas Taylor to review the situation; his report, released in 1887, found that Travis acted beyond his authority.

The Travis affair presented the Dominion government with the opportunity to reorganize the court system in the Northwest Territories in 1886. Stipendiary Magistrates became judges on the newly formed Supreme Court of the Northwest Territories (SCNWT). This new court handled more serious offences, while Justices of the Peace remained and dealt with lesser matters. The law in the Territories was based on English Common Law as of 1870.[12] However, Jean Côté, a former judge on the Alberta Court of Appeal, argued in a 1964 article in the Alberta Law Review that judges practiced discretion when applying English law and considered the social, economic, and political climate of the Northwest Territories, which, not unsurprisingly, was significantly different from England.[13]

All of this brought a more formalized administration of justice to the frontier. Macleod became aggravated with the new judicial system. The SCNWT became responsible for both the original and the appeal processes.[14] Macleod, however, reportedly favoured trial proceedings over sitting on appeal. It is believed he did not get along with his judicial colleagues, allegedly because the government elevated his former junior, Hugh Richardson, to precedence on the new court.[15] Also many of his rulings were overturned on appeal. An examination of these cases demonstrates that Macleod was weak on the technical aspects of the law. Though his reasoning was based on a sense of fairness, his judgements were subjective and not grounded in the law.[16]

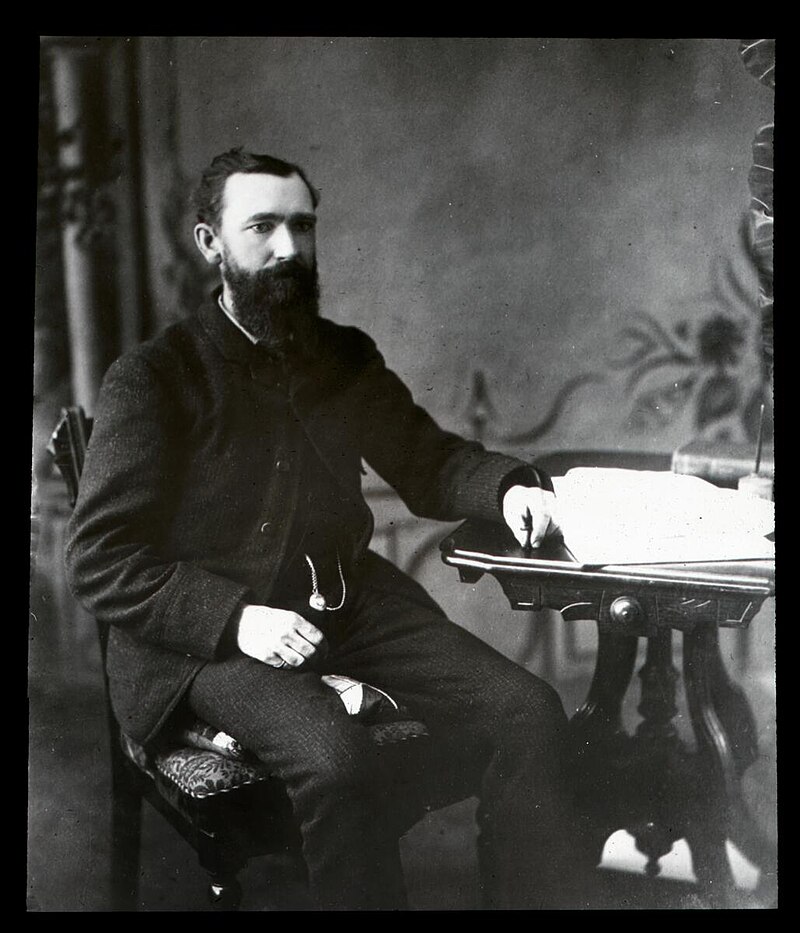

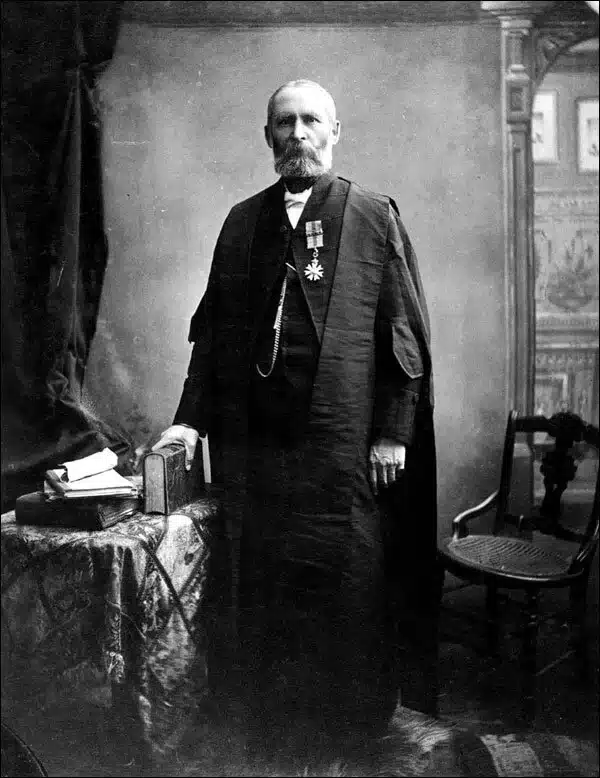

The restructuring divided the Territories into several judicial districts. Calgary became the headquarters of the northern Alberta district with Charles Rouleau as the resident judge. Born and educated in Lower Canada, he became a Stipendiary Magistrate in 1883 and was a Supreme Court Judge from 1887 until 1901. Unlike Macleod, Rouleau emersed himself in the law. He was regarded as the court’s most learned member and relied on his large collection of legal books to aid him in crafting his written decisions. A majority of his decisions that went to the appellate court were upheld.[17]

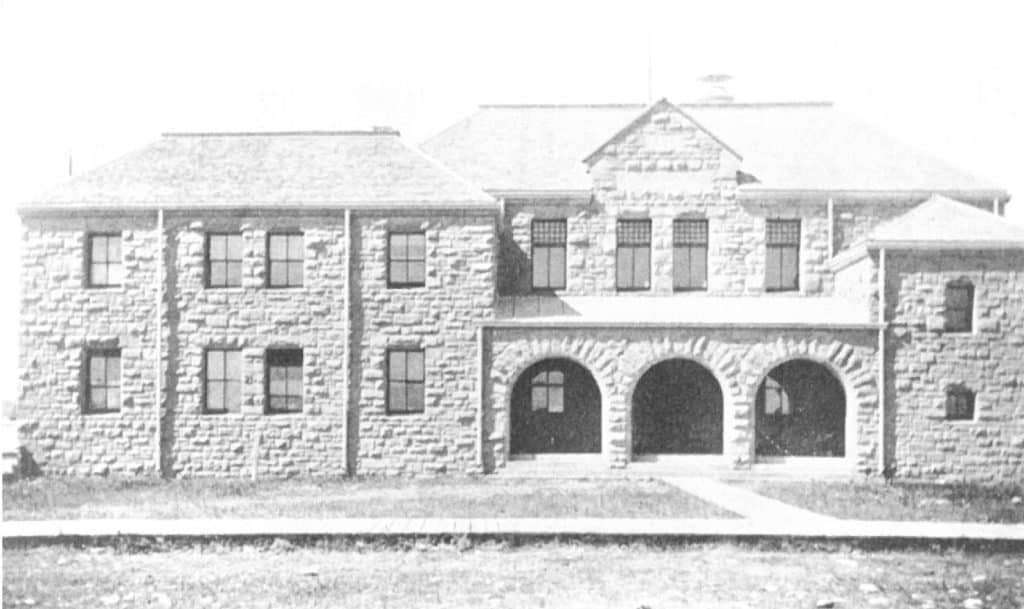

Even though a more structured system of judicial administration came to Calgary with the reorganization of the courts and the appointment of a permanent judge, Calgary still did not have a proper courthouse. While Macleod was willing to hold court in any available venue, the trial of William “Jumbo” Fisk in 1889 demonstrated that that immigration shed that was quickly outfitted in 1885 as a facility was no longer sufficient. Calgary needed a proper courthouse with prisoner cells, offices for judges and court employees, as well as a barrister’s lounge, and a jury room.

On August 13, 1890, the third stage of formal justice arrived in Calgary with the opening of the new Territorial courthouse. This courthouse was not just a building to administer justice, it was a symbol that came to represent the process of bringing order and civilization to the frontier.[18] The Territorial courthouse was replaced in 1914 with Calgary’s second courthouse. In the 1950s, it became apparent that Calgary needed a new modern courthouse, and the site of the Territorial courthouse seemed logical. Despite efforts to save the city’s first courthouse as a historic landmark, it was torn down in 1958 to make way for a new three million dollar courthouse.[19]

Between 1887 and 1907, there was a total of 521 reported cases heard by the SCNWT. Nearly eighty-five percent of these were civil cases. According to the Territorial Law Reports these included procedural applications, company law and private law issues on a range of matters dealing with negligence, damages, and breaches of contract.[20] Of these civil cases, the CPR was involved in a majority dealing with negligence and injury, destruction of cattle, and unsafe train operations. Arguably, the CPR is considered the most influence factor in the development of Territorial law during this period.[21] In court dealings with the CPR, judges practiced discretion, as Côté suggested. Matters dealing with carelessness leading to injury typically went against the company, which did not always follow well-established precedent. On the other hand, judges ruled in favour of the CPR in matters of business.[22]

Popular lore suggests that the frontier was crime-free. Certainly, in comparison to Canada’s southern neighbour, settlement of the west was far less violent. But that hardly means there was no violence and crime free. Of the 521 reported cases on the SCNWT docket, only fifteen percent dealt with crime. In the city of Calgary, cases dealt largely with cattle theft and crimes against property, petty theft, vagrancy, and morality crimes such as alcohol, gambling, and prostitution.[23] Violent crimes, such as murder, did occur during the period, including those involving Jess Williams, William “Jumbo” Fisk, and Ernest Cashel. According to reports and statistics, in a city of approximately 4,000 residents only ten murders were perpetrated before the turn of the twentieth century.[24]

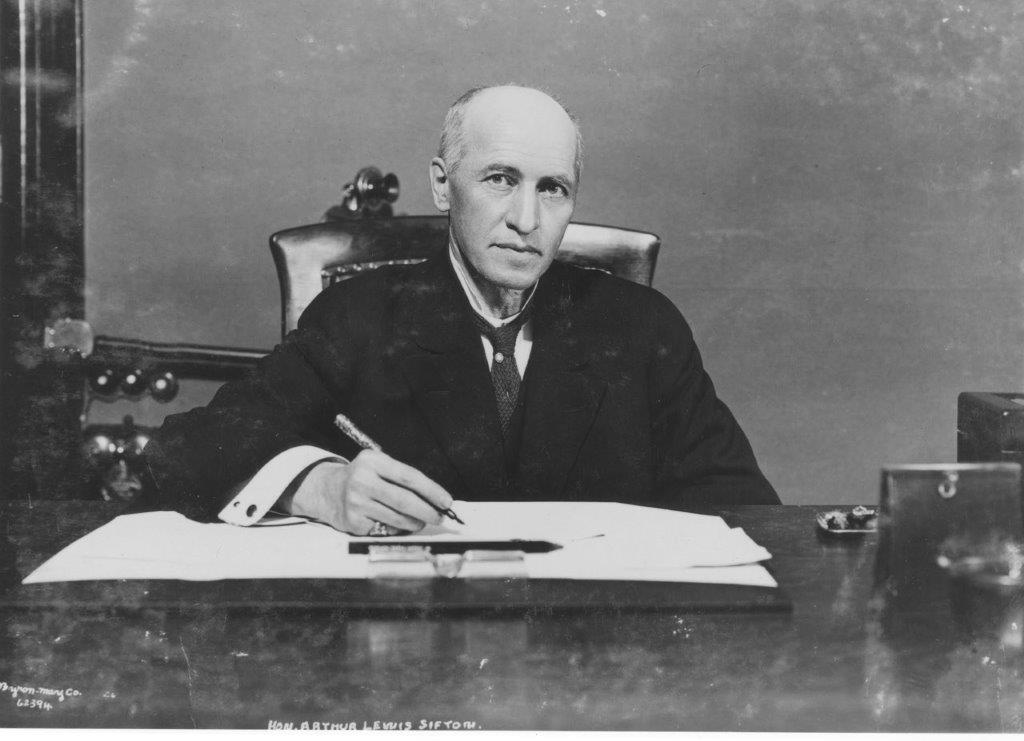

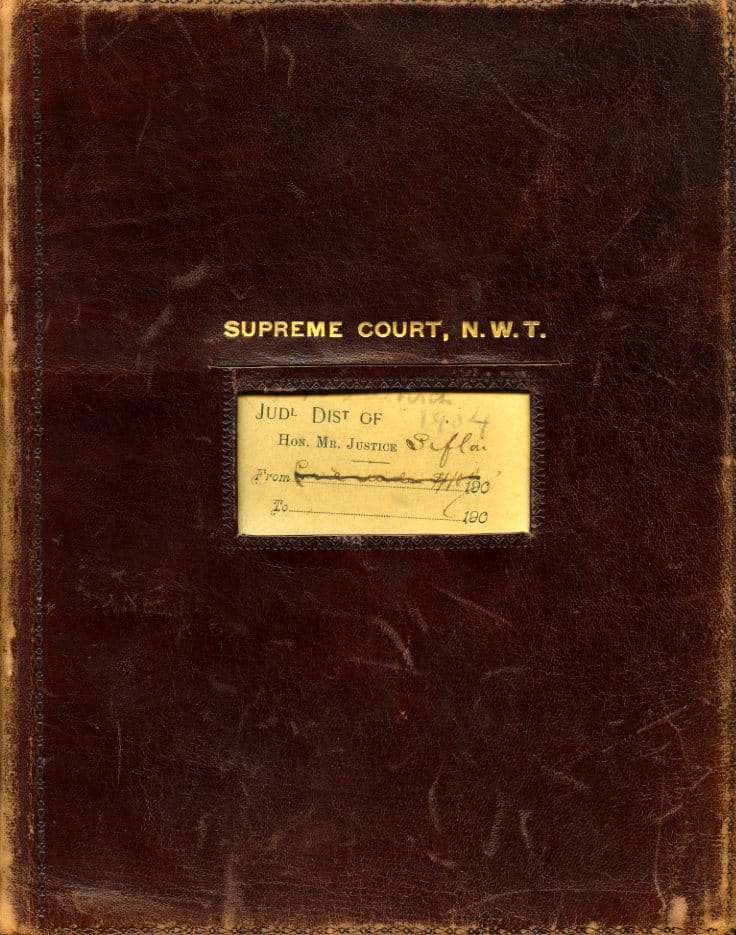

Judge’s notebooks from the period in question offer a glimpse into the types of criminal cases before the courts. Arthur Sifton, Chief Justice of the SCNWT from 1903 to 1907, maintained notebooks that reveal issues involving property damage, forgery, assault, incest, murder, and livestock theft. In fact, he became known as “a terror to the cattle rustlers and thieves of the west.”[25] He was considered pragmatic and well within the norms of sentencing guidelines, except when it came to dealing with livestock theft. Sifton believed that harsh punishment would act as a deterrent to future cattle thieves and typically sentenced offenders to three years in prison. In 1904, he condemned a Maple Creek rancher to four years in Manitoba’s Stoney Mountain Penitentiary for changing brands on cattle.[26]

His most famous case – The King v. Ernest Cashel – from 1903 and 1904 dealt with forgery, horse theft, and murder. Known as a young Jesse James, Cashel arrived in Alberta from Wyoming in 1902. He escaped custody by jumping from a moving train while on charges for suspicion of forgery. In June 1903, he was sentenced to three years in Stoney Mountain Penitentiary for horse theft.[27] After the body of Isaac Rufus Belt was found, he was once again brought before Sifton on charges of murder and sentenced to hang. With the help of his brother, John, who smuggled two guns in the NWMP barracks in Calgary, Cashel escaped. Sifton’s notebooks cover the escape over forty-two pages. While his brother John was captured immediately, Ernest was only recaptured on January 24, 1904, following a forty-two-day manhunt involving forty men. According to Sifton’s notebooks, Cashel’s execution was postponed three times because of the escape. He was only the second man to be hanged in Calgary on February 4, 1904, at the age of twenty-two.[28]

Conclusion

Law does not exist in a vacuum. It is influenced by the political, economic, and social environment in which it operates. It also shapes the society around us. We have seen how economics and politics led to the appointment of Calgary’s first resident judge, the city’s first courthouse, as well as the replacing and building of subsequent courthouses. We saw how politics and morality brought about changes in the administration of justice in the Northwest Territories. Though the law flowed from English Common law during this period, we saw that judges considered all these outside influences in both civil and criminal decision-making.

Alberta’s legal history, thanks to Wilbur Bowker, Horace Harvey, John McLaren, Louis Knafla, Rod Macleod, James Muir, and Lyndsay Campbell, has moved from beyond the periphery of the province’s history and has become the focus of several significant books and articles over the last twenty years. Calgary’s contribution has been, and will continue to be, noteworthy.

[1] R.C.B. Risk, “A Prospectus for Canadian Legal History,” Dalhousie Law Journal vol. 1, no. 2 (1973): pg. 227.

[2] Philip Girard, Jim Phillips, and R. Blake Brown, A History of Law in Canada, Volume One: Beginnings to 1866 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018), pg. 3.

[3] John McLaren, “Meeting the Challenges of Canadian Legal History: The Albertan Contribution,” Alberta Law Review vol. 32, no. 3 (1994): pg. 425.

[4] Ibid., pg. 428.

[5] Louis A. Knafla, “‘Law-ways and Law-jobs,’ and the Documentary Heritage of the State,” in Law, Society, and the State: Essays in Modern Legal History eds. Louis A. Knafla and Susan W.S. Binnie (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1995), pg. 443.

[6] Richard Klumpenhouwer, “Private Sector Legal Archives in Canada: A Sources of Concern,” in Ibid., pg. 498.

[7] David Mittelstadt, “Calgary’s Early Courts: Establishing our Justice System,” in Remembering Chinook Country: Told and Untold Stories of our Past ed. The Chinook Country Historical Society (Calgary: Detselig Enterprise Ltd., 2005), pg. 198.

[8] Henry C. Klassen, “Lawyers, Finance, and Economic Development in Southwestern Alberta, 1884 to 1920,” in Essays in the History of Canadian Law: Beyond the Law: Lawyers and Business in Canada, 1830 to 1930, Volume IV ed. Carol Wilton (Toronto: The Osgoode Society of Canadian Legal History, 1990), pg. 298-99.

[9] Mittelstadt, “Calgary’s Early Courts: Establishing our Justice System,” pg.199.

[10] David Mittelstadt, Foundations of Justice: Alberta’s Historic Courthouses (Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2005), pg. 18.

[11] Ibid., pg. 18.

[12] Louis A. Knafla, “From Oral to Written Memory: The Common Law Tradition in Western Canada,” in Law & Justice in a New Land: Essays in Western Canadian Legal History ed. Louis A. Knafla (Toronto: Carswell Company Ltd., 1986), p. 52-3.

[13] J.E. Côté, “The Introduction of English Law in Alberta,” Alberta Law Review vol. 3 (1964): pg. 270-72.

[14] Roderick G. Martin, “Macleod at Law: A Judicial Biography of James Farquharson Macleod, 1874-94,” in People and Place: Historical Influences on Legal Culture eds. Jonathan Swainger and Constance Backhouse (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2003), pg. 48-9.

[15] Louis Knafla and Rick Klumpenhouwer, Lords and Ladies of the Western Bench: A Biographical History of the Supreme and District Courts of Alberta, 1976-1990 (Calgary: Legal Archives Society of Alberta, 1997), pg. 93.

[16] Ibid., pg. 93 and Martin, “Macleod at Law,” pg. 51-2.

[17] Knafla and Klumpenhouwer, Lords and Ladies of the Western Bench, pg. 161.

[18] Mittelstadt, Foundations of Justice, pg. XVII.

[19] Ibid., pg. 28-9.

[20] Cited in Roderick G. Martin, “The Common Law and Justice of the Supreme Court of the North-West Territories: The First Generation, 1887-1907,” in Law and Societies in the Canadian Prairie West, 1670-1940 eds. Louis A. Knafla and Jonathan Swainger (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2005): pg. 211-212.

[21] Ibid., pg. 214-15.

[22] Ibid., pg. 217.

[23] T. Thorner, “The Not-So-Peaceable Kingdom: Crime and Criminal Justice in Frontier Calgary,” in Frontier Calgary: Town, City, and Region 1875-1914 eds. Anthony W. Rasporich and Henry C. Klassen (Calgary: McClelland and Steward West, 1975), pg. 101-03.

[24] Ibid., pg. 101.

[25] Arthur Sifton clippings files, Legal Archives Society of Alberta.

[26] Knafla and Klumpenhouwer, Lords and Ladies of the Western Bench, pg. 167.

[27] LASA Fonds 11-00-01, Vol. 1, File 1

[28] Ibid.