Stacy F. Kaufeld, M.A.

*Originally a speech presented to the Calgary Association of Lifelong Learners on January 22, 2024.

“Who is going to run this country, the Chief Justice or the Government?”[1]

This was a question put to deputy sheriff, John McCaffary by Major R.B. Eaton during the height of the conscription crisis in July 1918 at the Victoria Park barracks.

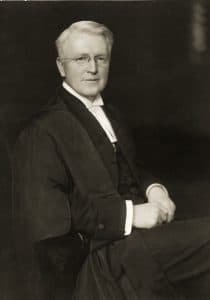

The Chief Justice in question was Horace Harvey. Considered a giant in Alberta’s legal history, his judicial career spanned forty-four years. The longest serving judge in Alberta’s history and possibly in Canadian history.

It was 1917 and the war had raged longer than anyone anticipated. Remember, most believed the war would be over by Christmas 1914. For nearly three years, Canada’s military contribution was voluntary. With no end in sight and mounting casualties, Parliament passed the Military Service Act in August 1917 allowing for conscription with special exemptions for essential jobs, such as farming.

For the most part, when we think of the conscription crisis, most immediately imagine the friction between French Canadiens and English Canadians. Certainly, a national crisis that was exacerbated by a prolonged war and growing personnel shortages.

But here in Alberta, opposition to conscription was not based upon loyalty to Great Britain. Despite introducing conscription in 1917, by the spring of 1918 there continued to be a shortage of military-aged men being sent overseas. Rather than amending the Military Service Act, the Governor in Council opted for two orders-in-council under the 1914 War Measures Act. This latter Act gave the Governor-in-Council wide power to make orders in the interest of national security during war.

Acting on the advice of cabinet, the two orders-in-council cancelled all exemptions under the 1917 Military Service Act, including those exempting farmers. The Alberta agricultural industry was also, because of the war, facing a manpower shortage. For these farmers the exemptions were necessary to continue growing food to support the war effort.[2]

This is the very basic background behind Chief Justice Harvey’s confrontation with military authorities in Calgary.

Norman Lewis was one of those farmers whose exemption was cancelled. His father was angered at the prospect of losing an invaluable farmhand and sought out R.B. Bennett. The future Prime Minister faced a difficult situation. Bennett supported conscription and voted for the Military Service Act. But as the Director of Mobilization during the war, he was aware of the difficulties facing farmers because of the cancelled exemptions.[3]

Bennett applied to the Supreme Court of Alberta for a writ of habeas corpus – an order to release a person whom the court determines is being held illegally. In this case, Bennett was arguing the military was holding Lewis illegally. He reasoned, in front of a five-judge panel, that the exemption cancellations were invalid because the orders-in-council granted under the War Measures Act were invalid.[4]

The majority of the judges (four to one) ruled that the exemptions could only have been stopped with an act of Parliament that amended the Military Service Act. Chief Justice Harvey dissented. The court ordered the immediate release of Lewis.[5] Harvey agreed to allow a two-week stay while the military authorities sought an expedited appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada.

This order put in motion a series of events that no one expected.

A second order-in-council was issued stating that the military would process men with cancelled exemptions, “notwithstanding the judgement and notwithstanding any judgement, or any order that may be made by any court.”[6] Until the Supreme Court of Canada heard the case, however, the Alberta Court’s ruling was the law of the land in this province. Essentially, the government was advising military authorities to break the law.

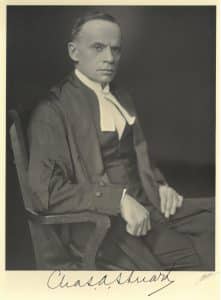

As a result of the court’s ruling, twenty other recruits from the Sarcee Camp applied by way of habeas corpus. Justice Charles Stuart ordered that military authorities were not to remove any of the applicants from Alberta’s jurisdiction. Counsel for many of the applicants claimed, in front of Chief Justice Harvey, that they felt Stuart’s orders were being disobeyed.[7]

Now for the plot twist. Despite having dissented in the original decision, Chief Justice Harvey was now defending his court and the majority. For him there was more at stake than this one judgement. Rather, the rule of law and the authority of the court was at risk.

Harvey ordered that the commander of the recruitment depot, Lieutenant-Colonel Moore, appear in court along with all the habeas corpus applicants. Instead, Major J.M. Carson, Assistant Judge Advocate General, appeared and told the court that Moore was under direct orders not to obey the court. Harvey, along with Justices Beck and Stuart, issued a writ of attachment – an arrest warrant – for Lieutenant-Colonel Moore.[8]

John McCaffary, Calgary’s Deputy Sheriff, went to the Victoria Park barracks to arrest Moore, and was prevented access to the Lieutenant-Colonel and the applicants by what Harvey could only call an “armed military resistance”.[9]

The Calgary Herald best described the encounter and it is worth quoting at length:

“Victoria Park Barracks…had been turned into an armed camp. The Strathcona Horse has been brought in from Sarcee Camp to guard headquarters. Armed guards have been placed at every vantage point…Partitions have been torn down and two machine guns placed that will sweep the open space in front of the building.”[10]

This is when Major Eaton asked deputy sheriff McCaffrey, “who is going to run this country, the Chief Justice or the Government?”

At this point, the court had two options. They could back down, which would demonstrate to the citizenry that the military had no obligation to respect the court. Harvey, however, determined that he had no alternative and ordered the sheriff to use force, if need be, to bring Colonel Moore to court.[11]

Sensing the growing tensions between the military and the court, Calgary city council became increasingly anxious about the potential for violence. H.P.O. Savary, a well-respected lawyer, appeared in court to seek a compromise on behalf of city council. He suggested a meeting between the civilian authorities, the lawyers, the acting mayor, Frank Freeze, and the military authorities.[12] Colonel Macdonald, district commanding officer, proposed a compromise whereby he gave personal assurance that he would not remove any conscripts without twenty-four hours notice, and Harvey suspended the writ.[13]

One week later, the Supreme Court of Canada heard a habeas corpus case from Ontario involving Edwin Grey. Similar in nature to the Lewis case from Alberta, Canada’s top court ruled that the order-in-council cancelling the exemptions was valid. Harvey was justified in his dissent.[14]

Notwithstanding the near showdown between the military and the court in the streets of Calgary, the significance of this event was Chief Justice Harvey’s conduct. Despite being in favour of conscription himself and dissenting in the Lewis case, he took it upon himself to enforce the law as his colleagues declared it. He defended the rule of law and the independence of the judiciary in the face of immense pressure.

[1] Wilbur F. Bowker, “The Honourable Horace Harvey, Chief Justice of Alberta,” The Canadian Bar Review vol. 32, no. 9 (November 1954): pg. 933.

[2] David Mittelstadt, People Principle Progress: The Alberta Court of Appeals First Century 1914-2014 (Calgary: Legal Archives Society of Alberta, 2014), pg. 69.

[3] Ibid., pg. 71.

[4] Ibid., pg. 71.

[5] James H. Gray, Talk to My Lawyer! Great Stories of Southern Alberta’s Bar & Bench (Edmonton: Hurtig Publishers Ltd., 1987), pg. 47.

[6] Bowker, “The Honourable Horace Harvey,” pg. 934.

[7] Mittelstadt, People, Principles, Progress, pg. 73.

[8] Ibid., pg. 73.

[9] Quoted in Bowker, “The Honourable Horace Harvey,” pg. 935.

[10] Quoted in Mittelstadt, People Principles Progress, pg. 73.

[11] Gray, Talk to My Lawyer!, pg. 51-2.

[12] Ibid., pg. 52.

[13] Bowker, “The Honourable Horace Harvey,” pg. 936.

[14] Mittelstadt, People Principles Progress, pg. 77.