Stacy F. Kaufeld, M.A.

Before there was the Honourable Mary Hetherington, the Honourable Catherine Fraser, the Honourable Mary Moreau, and the Honourable Sheilah Martin, there was Ruth Gorman.

Though she was only a lawyer for a short period and never a judge, Ruth was a warrior against injustice. She received her law degree in 1939 from the University of Alberta and, like many who never practiced, she used her knowledge of the law to help others in their battles for social justice.

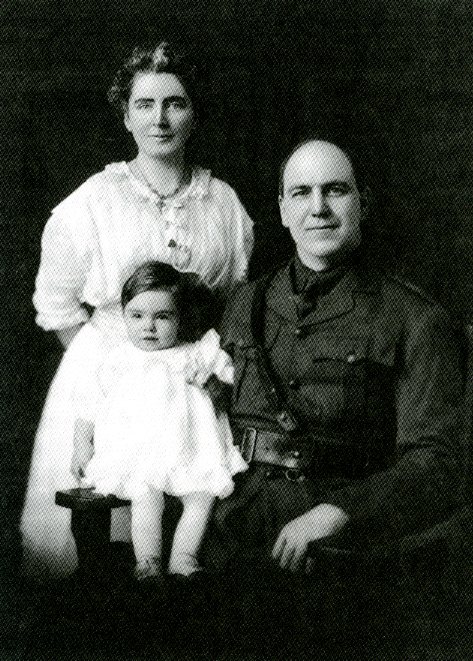

Ruth was born in 1914 and grew up in the Mount Royal neighbourhood of Calgary. Her father, M.B. Peacock, was a well-known Calgary lawyer and became close to the Indigenous communities surrounding Calgary after defending the traditional hunting rights of the Stoney while acting for William Wesley in R. v. Wesley in 1932. Before becoming involved in Indigenous activism, Ruth became an Indian Princess because of her father’s relationship with the Indigenous peoples.[1]

She never wanted to become a lawyer. In fact, Ruth purposely failed her Latin exams twice in high school in hopes of avoiding law school. But her father’s significant influence and having graduated from university during the height of the Great Depression motivated her to go to enrol at law school.

In a 1983 interview for the Calgary Bar Association, Gorman described her time in law school. He male classmates would take her to breakfast every morning, she explained “[t]hey’d flip a coin and the loser would pay for me! Just to keep me in my place! Oh they were funny: they hung me out the window once.”[2] She then recalled at a reunion, one of her classmates said, “we all fell in love with you, and we were glad that you finally choose one of us. My mouth fell open and I said: ‘[y]ou’re all just a bunch of liars! You hung me out a window!’.”[3] She did, in fact, marry her fellow classmate and Calgary lawyer, John Gorman on September 14, 1940.

Like many women from her generation, Ruth found it difficult to obtain articles. But became of her father, she was more fortunate than others acquiring a position with his firm. Following the completion of her articles, Ruth was admitted to the Law Society of Alberta on June 28, 1940. She only practiced, presumably at the same firm, for a short time before requesting a move to the non-practicing list on September 30, 1940.[4] Her daughter, Linda, also a Calgary lawyer, was born on July 17, 1941.

Though she was a young mother and did not return to practice, Ruth remained active and devoted to several causes, and she often used her knowledge of the law to benefit those matters. She gave advice and guidance to the many organizations she was associated with including the Local Council of Women, the Canadian National Council of Women where she worked on amendments to Alberta’s Dower Act, which prevented the disposition of the marital home without the wife’s consent. Gorman was also involved in establishing Calgary’s Indian Friendship Centre and the Calgary Rehabilitation Centre for the Handicapped.

One such occasion where she used her law degree was fighting to prevent the city’s planned relocation of the CPR to the south bank of the Bow River. Mayor Harry Hays, Gorman explained, signed a deal with the railway to take over what she described as the “best property in Calgary!” The planned route was over Prince’s Island. Ruth explained, “it was the most terrible contract I’ve ever seen in my life…I nearly fainted dead away because no one in the City Council had read the contract.”[5]

To bring awareness of the deal to Calgarians, Gorman tried to publish letters to the editor in the Albertan and the Herald. Because both owners had financial interests in the CPR she was rebuffed. She remained persistent and a letter was eventually published, and the railway claimed it was all falsehoods. In response the Local Council of Women set up and hosted what was essentially a town hall meeting that included four councillors and the Mayor. Though the CPR was invited, no representatives attended to explain how Ruth was misinformed nor to speak to the benefits of the deal. Eventually the deal fell through after a hearing was held at the Legislature in Edmonton and, as a result, Calgarians are still able to enjoy Prince’s Island.[6]

Arguably her greatest achievement came after meeting John Laurie and becoming involved with the Indian Association of Alberta. Laurie, a Calgary-area school teacher, devoted much of his spare time to Indigenous issues. After realizing that the Indigenous people did not completely understand the document that essentially governed their relationship to Canada, he invited a group of Calgary lawyers to help explain the Indian Act to several southern Alberta Chiefs. However, only Ruth Gorman showed up. Following a two-day seminar, Ruth took on a role that would occupy the better part of the next twenty years.

In 1951, the federal government passed bill 79 which would essentially make changes to who could claim Treaty rights and live on reserves. It allowed any ten members of a band to protest the membership of any individual based on parentage.[7] It is unclear why Ottawa chose this moment to redefine who was considered Indigenous through amendments to the Indian Act, but it was almost immediately used to question the ancestry of twenty-seven people from two different families. In January 1952, ten members of the Samson Band accused members from these families of failing to meet the criteria for full Treaty rights. The protesters alleged that three ancestors from these two families accepted Metis script.[8]

Evidence against John Samson was a telegram from Ottawa unveiling the accused had applied for script. Legally, this was all the Band need to expel Samson. Gorman, however, demanded the complainants produce actual evidence. When the documents arrived, they were stamped “application refused”. The commissioner appointed by Ottawa had no choice, but to reject the application for expulsion.[9]

The federal government was not satisfied and passed an order-in-council amending the Act to essentially call for the defendants to prove none their ancestors took script. An almost impossible task. Before returning to the courts in February 1956, Ruth called upon some of her former classmates, John Gorman, Robert Barron, A.F. Moir and Joe Brumlick, to represent Samson in this uphill battle.[10]

In what was a process that seemed stacked against the defendants, the original decision was overturned the two families were ordered off the Band roles. The story does not end there. There was a plan to appeal. For Gorman, it was an appeal to both the courts and public opinion. However, to take advantage of the press, Gorman, in another ingenious legal maneuver, opted to not officially file an appeal until the last possible moment. This allowed this vital issue to be fully disclosed and discussed in the court of public opinion.

On March 1, 1957, Chief Judge Neils V. Buchanan of the North Alberta District Court put an end to the government’s longing to assimilate Indigenous people.

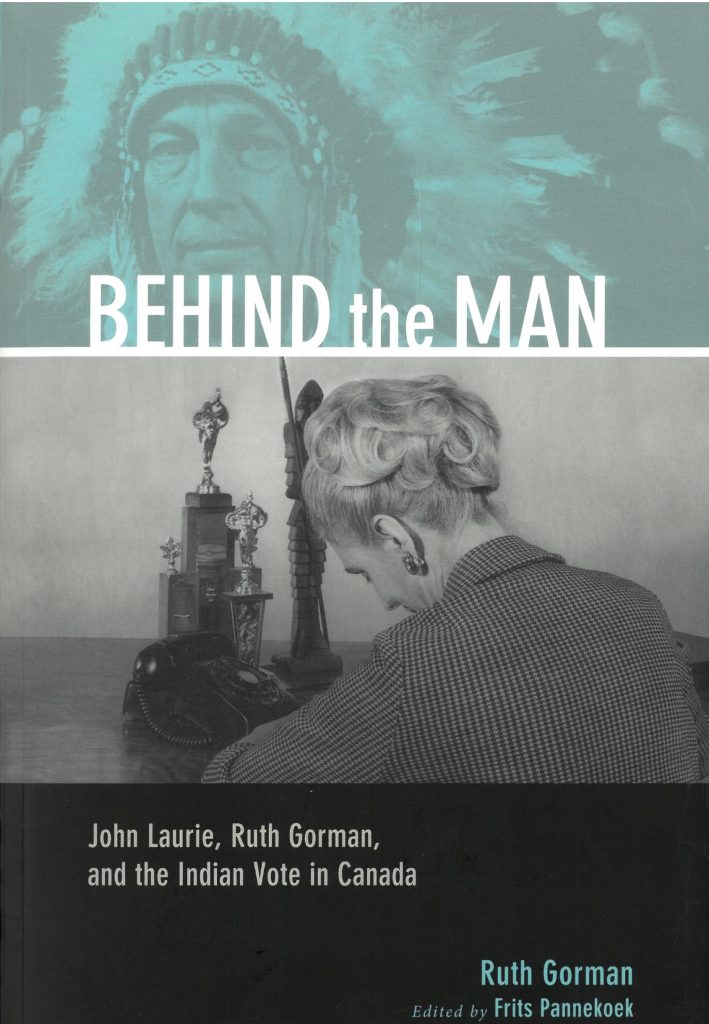

In 2007, Frits Pannekoek edited a manuscript Ruth was working on about John Laurie. Inasmuch as it was a biography of John Laurie, it was also an autobiography of Ruth Gorman. The book, Behind the Man: John Laurie, Ruth Gorman and the Indian Vote in Canada was a long-term project for Ruth. It was here where she described the dispute to obtain voting rights for Indigenous communities without losing their treaty rights and special status.

John Laurie died in 1959 before the change to Indigenous voting status and, as historian Frits Pannekoek writes, “Gorman saw it as her mission to change the Indian Act. Section 112, compulsory enfranchisement, had to be removed.”[11] Because of Ruth Gorman’s efforts, Indigenous peoples were able to retain their Treaty rights, as well as remain living on their reserves. By securing changes to the Act 1961, they would no longer be “forcibly enfranchised” in order to vote federally.[12]

Gorman was a modest woman and gave much credit to Laurie and believed that he has been overshadowed in Alberta’s history and the struggle for Indigenous equality. As the book correctly illustrates, Gorman’s contributions were equally important to those of Laurie. As all book biographies/autobiographies do, they put their subject(s) into the context of the time. Ruth Gorman was fighting for Indigenous equality at a time when nations around the world began to take human rights seriously, including Canada. In fact, in 1960, under Prime Minister Diefenbaker, Canada introduced its first Bill of Rights.

Without a doubt, Canada has had a long, tough road of reflection when it comes to relations with the nation’s Indigenous communities. Altering the Indian Act to allow Indigenous voting without sacrificing their Treaty rights was arguably, at the time, a reluctant step for the federal government. When we consider that only four years earlier Ottawa was using an order-in-council to further define and restrict who was considered Indigenous, the repealing of section 112 was on the right side of history.

Ruth Gorman was named woman of the year in Calgary in 1960, Citizen of the Year in 1961, Alberta Woman of the Century in 1967, and was awarded the Order of Canada in 1968, the first year it was presented. She passed away in 2002.

[1] Ruth Gorman, edited by Frits Pannekoek, Behind the Man: John Laurie, Ruth Gorman, and the Indian Vote in Canada (Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2007), pg. xxiii-xxiv.

[2] LASA Fonds 09-00-05, vol 11, no. 73.

[3] Ibid.,

[4] LASA Fonds 05-00-01, vol. 550, no. 3939.

[5] LASA Fonds 09-00-05, vol 11, no. 73.

[6] Ibid.,

[7] Frits Pannekoek, “A Strong-Minded Woman: Ruth Gorman,” in Remembering Chinook Country: Told and Untold Stories of our Past ed. The Chinook Country Historical Society (Calgary: Detselig Enterprises Ltd., 2005), pg. 87.

[8] Douglas Sanders, “The Queen’s Promises,” in Law & Justice in a New Land: Essays in Western Canadian Legal History ed. by Louis Knafla (Toronto: Carswell, 1986), pg. 116.

[9] James H. Grey, Talk to My Lawyer: Great Stories of Southern Alberta’s Bar & Bench (Edmonton: Hurtig Publishers Ltd., 1987), pg. 172.

[10] Ibid., pg. 172-73.

[11] Pannekoek, “A Strong-Minded Woman,” pg. 88.

[12] Gorman, Behind the Man, pg. xiv.