Stacy F. Kaufeld, M.A.

Arthur Sifton was born in St. John’s, Middlesex County, Ontario on October 26, 1859. He had a strict Methodist upbringing and was schooled in London, Ontario along with his younger brother, Clifford. The Sifton family relocated to Winnipeg after his father received a large railway contract from the Liberal government under Alexander Mackenzie.

GA NA-1328-62394

Arthur entered law and articled with A. Monkman, a Winnipeg lawyer, beginning in 1875. After receiving his BA from Victoria College in Toronto, a devoutly Methodist institution, he was admitted to the Manitoba bar in 1883 and practiced with his bother in Brandon, Manitoba. He was also elected City Counsellor in Brandon.

In 1884, Sifton moved to Prince Albert, Saskatchewan where he founded a loan company and was very active in the temperance community. He also wrote for the local newspaper and received an MA and LL.B from Victoria College in 1888.

In September 1882, he married Mary H. Deering of Cobourg, Ontario and they had two children together, a daughter, Nellie Louise and a son, Lewis Raymond St. Clair. Because of his wife’s persistent health issues, the Sifton family moved to Calgary in 1889.

Once he established himself in Calgary, he put out his shingle on Stephen Avenue and often acted as a Crown Prosecutor. Sifton also did some work in the city solicitor’s office and, as Calgary continued to grow, drafted the Charter for Calgary formalizing its status as a city in 1894. In 1901, he continued his work with the Crown after opening his firm, Sifton, Short, and Stuart. Though he was becoming an experienced lawyer, political office continued to beckon Arthur. He was elected as the Liberal representative for Banff in the Territorial Legislature from 1898 to 1902, where he was Treasurer and Commissioner of Public Works in the Haultain government from 1901 to 1903.

Following the resignation of Thomas McGuire, the Chief Justice of the Northwest Territories, Sifton was appointed to replace him in 1903. Calgary was without a resident judge for nearly three years following the death of Justice Charles Rouleau in 1901. Sifton became the city’s resident judge while also doing some circuit work. He was made Chief Justice of Alberta in September 1907 when the province launched a separate court system. With his family’s strong ties to the Liberal Party, many critics intimated that his judicial appointment by Liberal Prime Minister Wilfred Laurier was undeserved and crass political patronage.

As a judge, Sifton was not considered remarkable. In nearly seven years on the bench, he only authored two majority opinions. Judicially he was pragmatic and often remained unreadable on the bench, earning a ‘sphynx-like’ reputation from his contemporaries.[1] His judgments were always prompt following the conclusion of arguments, and were primarily oral without extensive reasons. As a result, it was a challenge for counsel to appeal. Finally, his judgments were considered a mixture of common-sense pragmatism and social morality and were rarely overturned.[2]

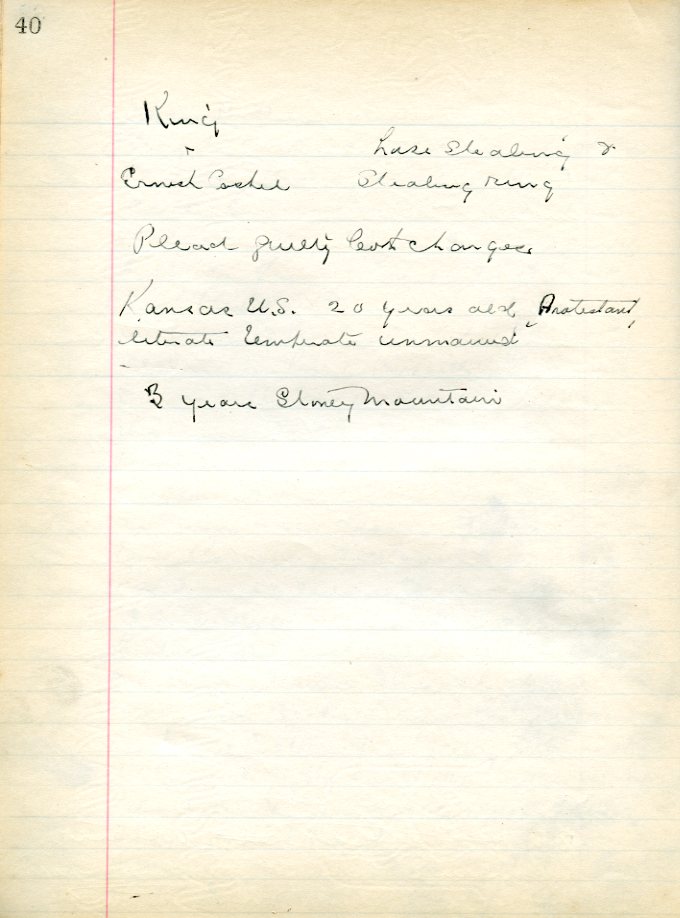

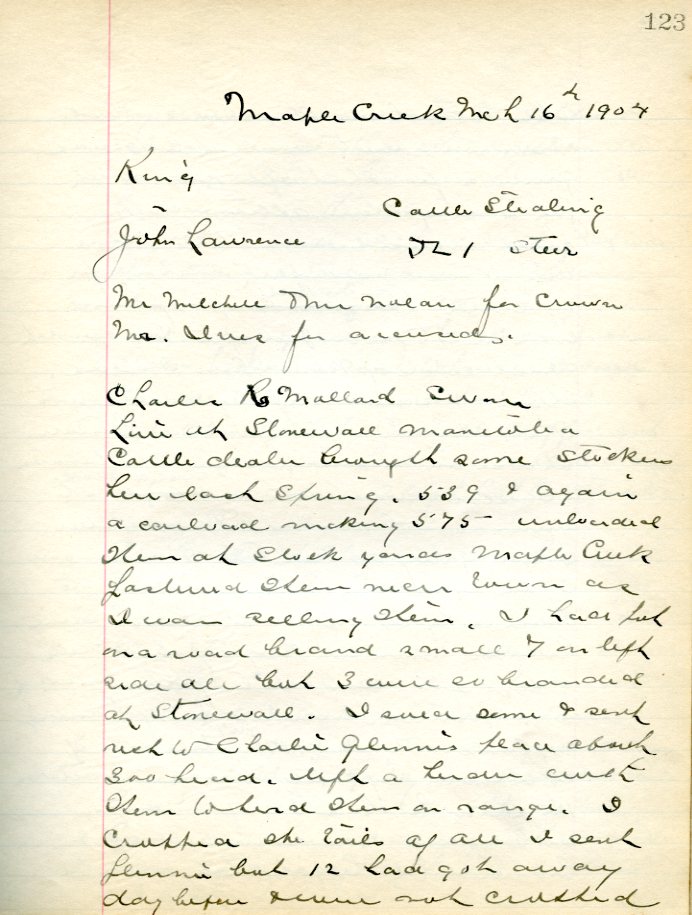

Sifton’s original notebooks describe many of the trials he sat on between 1903 and 1906. Likely reflective of the courts in general, he dealt with issues involving property damage, forgery, assault, incest, murder, and livestock theft. The first cattle herds arrived in southern Alberta around 1877, and theft became a growing problem by the time Sifton was on the bench. He became “a terror to the cattle rustlers and thieves of the west.”[3]

LASA Fonds 11-00-01, Vol 1, File 2

Sifton’s sentencing, like his judgments, was considered practical and aligning with social norms. However, when it came to combatting the growing theft of livestock, he was decisive and perhaps unforgiving. Possibly thinking harsh sentences would act as a deterrence to this growing problem, Sifton typically sentenced cattle thieves to a minimum three years in prison. For example, in R. v. Lawrence in 1904, he sentenced a Maple Creek rancher to four years in Stony Mountain Penitentiary for changing brands on cattle.[4]

LASA Fonds 11-00-01, Vol 1, File 2

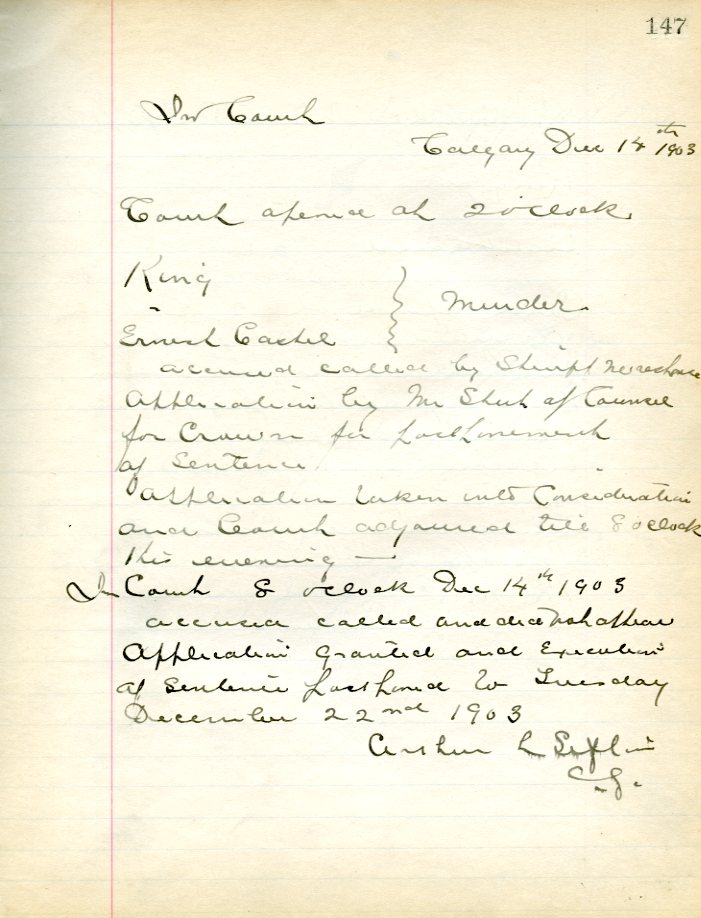

Arguably Sifton’s most famous trial took place in Calgary between 1903 and 1904. In The King v. Ernest Cashel, the case involved forgery, horse theft, and murder. At the time, the press glorified Cashel, who arrived in Alberta from Wyoming in 1902, as a young Jesse James – the infamous American outlaw, bank and train robber. While in custody for suspicion of forgery, Cashel escaped through a washroom window on a moving train. In June 1903, he was brought before Sifton on charges of horse theft and sentence to three years at Stony Mountain Penitentiary.

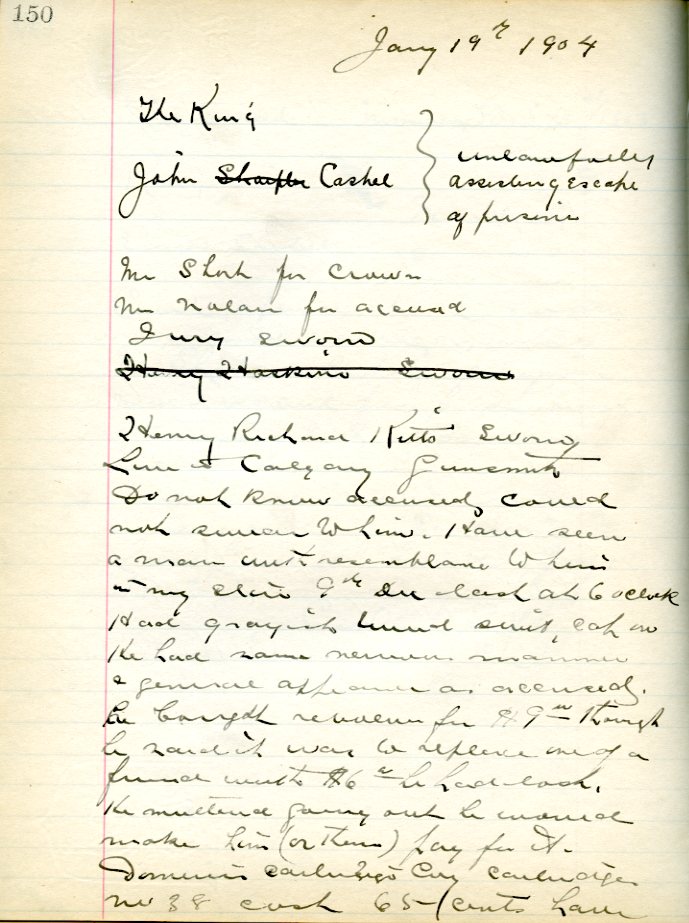

The body of Isaac Rufus Belt was discovered, and authorities linked the murder to Cashel. He was again brought before Sifton on charges of murder. He was convicted and sentenced to hang. However, five days before his execution date Cashel escaped NWMP custody at Calgary after his brother, John Cashel, smuggled him two guns. John was immediately caught and convicted of helping a prisoner escape. Sifton’s notebooks contain forty-two pages detailing the jail break. Cashel was recaptured on January 24, 1904, after a forty-two-day manhunt involving forty men. Sifton, in his notebooks, recorded three postponements for the executions because of Cashel’s escape. He was only the second man to be hanged in Calgary at the age of twenty-two on February 4, 1904.

By 1910 the Liberal Party was embroiled in a scandal involving the Alberta and Great Waterways (A & GW) Railway. It split loyalties within the Alberta Liberal caucus and eventually led to the downfall of Premier Alexander C. Rutherford. With the opposition Conservatives waiting impatiently to form government, Liberal Party insiders knew they needed a unifying figure to replace the disgraced Rutherford. Arthur Sifton was approached and, despite his position as Chief Justice, he decided to accept the offer. On May 17, 1910, he stepped down as the province’s top judge and was sworn in as Premier.[5]

His premiership, which lasted seven years, was dominated by several issues, including dealing with the fallout from the A & GW Railway scandal and expanding the province’s rail system. Sifton also developed Alberta’s rural telephone system. Most significantly, he began negotiating with the federal government over provincial control of its natural resources and public lands. And, in addition to the opposition Conservative Party, the United Farmers Association was growing in strength among Alberta’s predominantly agrarian population.[6]

Sifton was able to win a second term in the April 1913 election. It was only just over one year later that World War One broke out in August 1914. Though the country, including Alberta, was focused on contributing to the war effort both overseas and on the home front, Sifton tackled several significant issues. The Premier was long-time advocate of temperance and was in favour of prohibition but stopped short of legislating morality. However, with 23,600 people signing a petition in favour of prohibition, Sifton opted to put the matter to the people directly in a referendum held on July 21, 1915, with 58,000 in favour and 37,000 against. Notably, only men were allowed to vote after Sifton turned down the request for women to be included.[7]

This may be considered surprising given the Premier’s support for women’s equality. His government passed the Widow’s Relief Act in 1910, the Women’s Home Protection Act in 1915, which was replaced by the Dower Act in 1917. Sifton’s government appointed the first female magistrates – Emily Murphy and Alice Jamieson – in Canada in 1916. These appointments were upheld by the Supreme Court of Canada in R. v. Cyr in 1917. It was certain that Sifton was sensitive to women’s equality, so it is not clear why he was reticent when it came to suffrage. Whether because of women’s lobbying efforts or seeing the political future, Alberta, under Sifton, granted women the vote in 1916.

In October 1917, Sifton resigned his premiership and joined Prime Minister Robert Bordon’s Union government. He was elected as the Medicine Hat representative in Ottawa in December 1917. Despite his declining health, he was given a few minor responsibilities and was part of the Canadian delegation to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. His health continued to decline, and he passed away on January 21, 1921, in Ottawa at the age of sixty-one.

[1] Louis A. Knafla, “The Supreme Court of Alberta: The Formative Years, 1905-1921,” in The Alberta Supreme Court at 100: History and Authority ed. by Jonathan Swainger (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 1907): pg. 35.

[2] Louis Knafla and Rick Klumpenhouwer, Lords of the Western Bench: A Biographical History of the Supreme and District Courts of Alberta, 1876-1990 (Calgary: Legal Archives Society of Alberta, 1997), pg. 167.

[3] Arthur Sifton clippings file, Legal Archives Society of Alberta.

[4] Knafla and Klumpenhouwer, Lords of the Western Bench, pg. 167.

[5] David Hall, “Arthur L. Sifton, 1910-1917,” in Alberta Premiers of the Twentieth Century ed. by Bradford J. Rennie (Regina: Canadian Plains Research Center, 2004), pg. 25.

[6] Ibid., pg. 26.

[7] Ibid., pg. 34.