By Neil B. Watson

The following is a post written by Neil B. Watson, retired Calgary lawyer and former LASA Board Member, and is adapted from his original chapter on John McKinley Cameron, K.C., available in Citymakers: Calgarians after the Frontier, edited by Max Foran and Sheilagh Jameson.

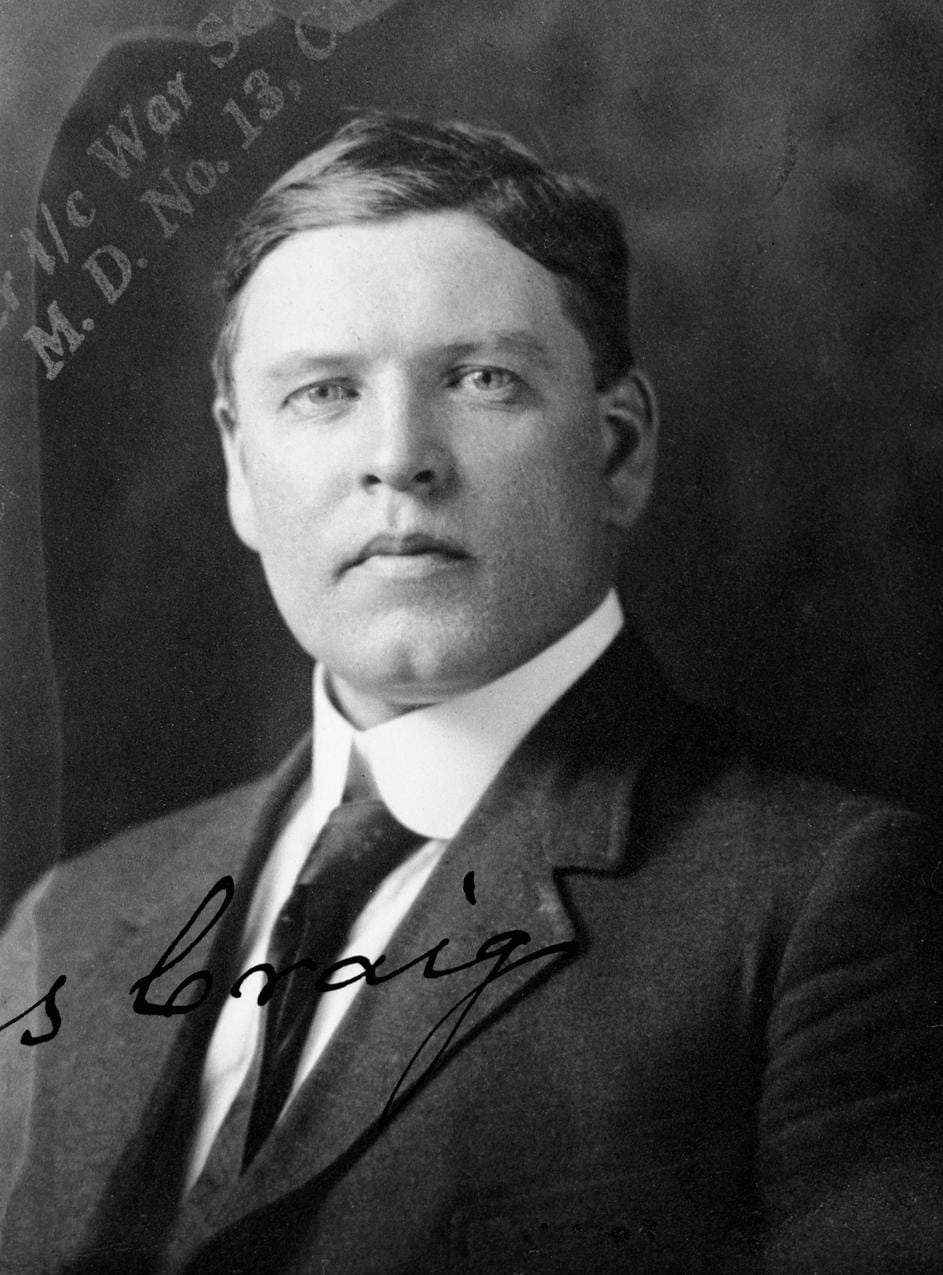

The economic boom in Calgary prior to the First World War was a magnet to scores of young professionals from Central Canada and the Maritimes. Not least among those drawn in search of opportunity and prosperity were members of the legal profession. One of the many who arrived in the city between 1908 and 1912 was John McKinley Cameron, an ambitious young lawyer from Nova Scotia. Within the short space of ten years, Cameron had become not only successful, but firmly established among the city’s business and legal elite. At the height of his career, he achieved the stature of the leading and most sought after defence counsel in Calgary and was recognized as one of the finest barristers in Western Canada.

McKinley Cameron was born in Pictou, Nova Scotia, February 24, 1879. Following graduation from high school in 1897 with borderline grades,he attended Pictou Academy and subsequently Dalhousie University, where he received degrees in Arts and Law. Cameron entered into articles with prominent Pictou lawyer Edward Mortimer McDonald in October of 1900. He completed his clerkship in March of 1904 and was admitted to the Nova Scotia Bar later that year. He first seriously considered moving west following a tour in 1907. Cameron had been impressed by the seemingly unlimited possibilities for a person with energy and ambition and the idea of “trying his fortune” greatly appealed to him. In 1911, at the age of thirty-two, he left his Nova Scotia law practice to his former partner and joined the Calgary firm of Stewart, Tweedie and Charman at a salary of one hundred dollars a month.

Financially, the first few years appear to have been difficult. The normal expenses facing any young lawyer starting up a practice with little capital, from law society fees to even a basic library, could be onerous. There was also, however, the combined strain of some unsettled personal debts which Cameron owed in Nova Scotia plus the prospects of a family. In May of 1912, his wife of one year, the former Ethel Munro, gave birth to the couple’s first son Stewart. Through the summer and fall of that year, their financial situation was strained; even the payment of rent for a modest home on 15th Avenue W. was posing considerable difficulty. Presumably to augment the income from his legal practice, Cameron co-lectured a course in criminal law, procedure and evidence, with James Short and Lloyd Fenerty at the fledgling Calgary College Law School.

Cameron’s association with the firm of Stewart, Tweedie and Charman was relatively short-lived. His partners had begun to direct more of their attention to investment opportunities in Turner Valley than the practice of law, and in June of 1914 the three lawyers agreed to go their separate ways. In the spring of 1914, with an office in the Alberta Corner, Cameron hung out the shingle of the solo barrister’s practice which he maintained throughout his career.

In 1920, he served as counsel for the defence in his first case of murder. On July 22 of that year, James Royce had been charged in the death of Anna Gordon, a prostitute with whom he had been living for some time.Like most murders, the Royce case attracted considerable interest among the public and a large crowd poured downtown to the Seventh Avenue police building to witness the accused’s arraignment. With skill and apparent ease, the defence attorney exposed a number of serious weaknesses in the Crown’s case of largely circumstantial evidence. At the end of the fifth day the jury retired for twenty minutes and returned with a verdict of not guilty, one with which the presiding judge wholeheartedly agreed.

Cameron’s reputation as a successful attorney grew steadily and by the early 1920s, the loss of a case handled by him was a rare enough occurrence to attract comment. A large part of that talent lay in a phenomenal grasp of criminal case law. Some colleagues concluded that no lawyer in Canada had so complete a command of the subject. In the summer of 1921, the year following the Royce case, Cameron was “given the silk” by the Alberta government and thus entered into that distinguished group of King’s Counsellors

Though the bulk of Cameron’s work involved the normally routine and undramatic criminal cases summarily disposed of in police court, to the public his name became synonymous with the sensational “front page” murder trials. Ironically, the case which attracted perhaps the most notice was the barrister’s most bitter defeat. The trial of Emilio Picariello and Florence Lassandro, held in Calgary between November 27 and December 22, 1922, received attention not only in Alberta but across the country. The pair had been arrested in Coleman on September 22 of that year charged with the murder of Alberta Provincial Police constable Stephen Lawson. The shooting of a policeman, then as now, was regarded as a particularly odious act. Also, Picariello was a well known bootlegger and the shooting had arisen out of an illegal liquor running incident. In 1922, at the height of prohibition, public opinion was sharply divided on the legislation’s effectiveness and the case became a focus for debate of the issue. Piquing interest further was the fact that one of the defendants was a woman and a woman had not been hanged in Canada for twenty-one years. Cameron was well aware of the importance of the case and he eagerly rose to the challenge. Assisting him in the defence were Sherwood Herchmer, Joseph Gillis and Donald Mckenzie. Across the court room floor the Crown was represented by Alex A. McGillivray K.C. and Samuel J. Helman.

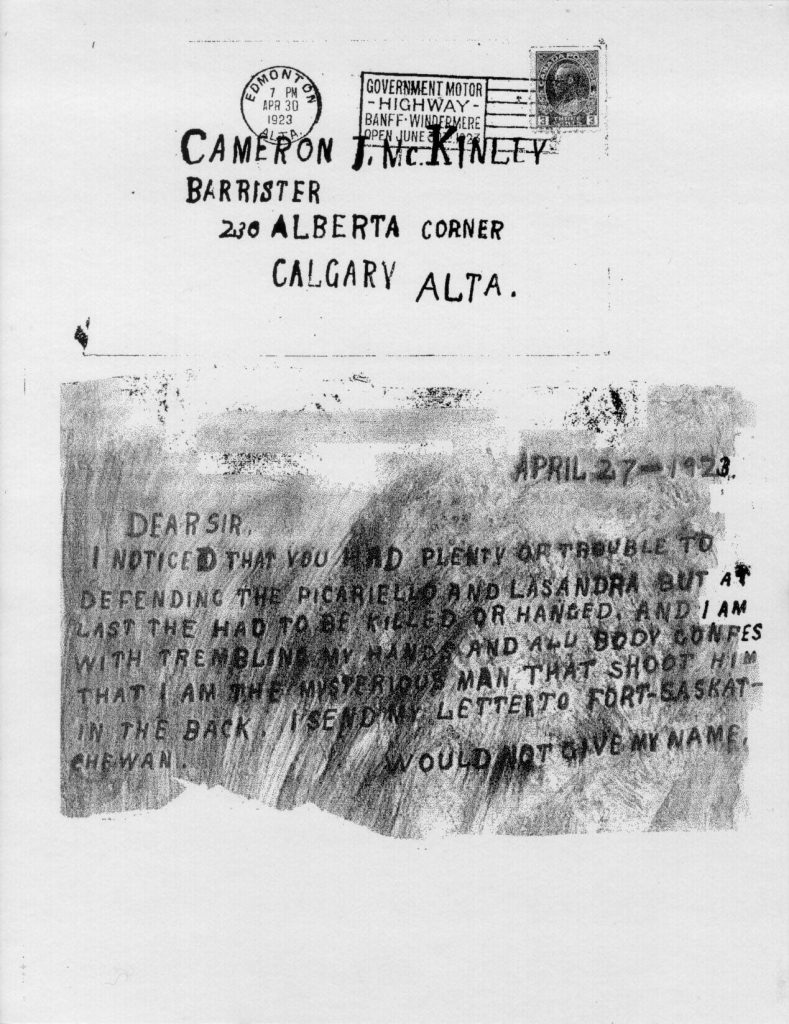

Cameron was personally convinced of the innocence of both his clients. He believed that neither Picariello nor Lassandro had even fired the fatal shot, much less done it with intent. Unfortunately, the “mystery by-stander” whom Cameron concluded had committed the crime was never identified or apprehended and the argument presented in court, also reasonably consistent with the facts, was self defence. The jury of six men, however, was unconvinced, and on December 2, 1922, it returned a verdict of guilty. Mr. Justice Walsh passed the obligatory sentence of death on both prisoners and set the date of execution for February 21, 1923. Believing that Justice Walsh had made several serious and even “fatal” errors, particularly in his charge to the jury, Cameron, on his clients’ instructions, took the case to the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of Alberta. It was dismissed, but because there was one dissenting opinion, a further appeal was allowed, this time to the Supreme Court of Canada. Although some of the judges wavered, the decision went unanimously against a new trial and upheld the original conviction. Bitterly disappointed, but determined to exhaust any remaining avenues, Cameron stayed in Ottawa making personal representations for a further reprieve or commutation of sentence. There was in fact very little which could still be done and on May 2, 1923, five days after notification that the Governor-General would not commute either sentence, Emilio Picariello and Florence Lassandro met their fate on the Fort Saskatchewan jail gallows.

Firmly convinced that two innocent people had gone to their death, the experience was difficult for Cameron and remained a painful recollection for many years. As senior defence counsel, he of course accepted some of the responsibility for the outcome personally. Beyond that, however, Cameron laid the blame squarely with the judicial system. He concluded that his clients simply had never received a fair trial and it was his fervent hope that some day the truth of their innocence would emerge, to serve as “a warning” and possibly prevent another such tragic mistake.

In private life, the tenacious and intense defence lawyer was a quiet, pleasant family man, always quick to display a keen sense of humour. From his large and impressive library he read on a wide variety of subjects with particular interest in political systems and British history. For relaxation, Cameron enjoyed playing checkers and occasionally participated in organized tournaments.He also sketched, a talent shared by his eldest son Stewart, who went on to become staff cartoonist for the Calgary Herald. Stewart always maintained however, that his father was a “better cartoonist than he.” Cameron enjoyed entertaining and was a gracious host. One family friend recalled pleasant evenings in his Mount Royal home, where as a rule, following dinner, the men would retire to the library and engage in friendly but animated debate, one of the favorite subjects being politics.

By the late 1930s, although still carrying on an essentially criminal practice, Cameron had acquired the reputation of being one of the shrewdest divorce lawyers in the province. He began appearing in divorce court as the “guide, philosopher and friend” of the parties involved, and his correspondence files contain hundreds of letters from potential clients inquiring about the likelihood success if an action was commenced. As a senior member of the legal fraternity whose experience in a number of specialized areas of the law was greatly respected, his opinion was also regularly sought out by other barristers.

In 1937, at the age of fifty-eight, Cameron appeared in his final murder trial, defending Albert Farrar, a young farmer from the Olds area. Farrar had been charged following the shooting death of his father during an argument over money. After a lengthy preliminary examination, the case came to trial in Calgary on October 25, before a criminal assize court judge and jury. Through Cameron’s gruelling and effective cross-examination, combined with a superb knowledge of the law, the testimony of even the Crown’s expert witness was cast into doubt. On Saturday, October 30, following what presiding Judge R.W. Howson described as a “long and troublesome case, ” Albert Farrar’s jury returned with the welcome finding of not guilty.

To the end of his career, Cameron was sought out as defence counsel in capital cases, but the emotional and psychological strain of assuming the responsibility for people’s lives had taken its toll over the years. By 1940, he frankly admitted to having come to a point where it simply took too much out of him and as a result he lost much of his relish for the challenge.When invited to handle a murder trial in Fernie, British Columbia that year, he agreed somewhat reluctantly, and on the condition that arrangements were made for the certain payment of his fee. But the accused man’s defence fund fell short of the agreed amount, allowing the barrister, perhaps with a sense of some relief, to withdraw from the case.

Cameron’s sudden and unexpected death at age 64 of a heart attack in April of 1943 cut short a most remarkable career. Though Calgary before the First World War had offered great promise to the host of young lawyers who arrived at that time, there was never any guarantee of success. A small number, including Cameron, went on to achieve distinction in their chosen profession. Over the course of his career, McKinley Cameron’s brilliant and effective defences had commanded the respect of colleagues and clients alike and enthralled a generation of courtroom spectators. Though he had experienced defeat, he had tasted victory more often and on that record had risen to prominence.

Having found success, he in turn was sympathetic and encouraging to young lawyers who wished to follow in his path. , He once advised, ‘ ..if you have a strong notion of coming west, you should by all means…it will have an unsettling influence for you…in your practice.. .and you will probably always think that you would have done very much better in the west. ” Whether or not Cameron was content with all the turns his career had taken, he could take satisfaction in knowing that he had the ambition to follow his own advice.

(Post Script: In February of 2003, Cameron’s 1922 trial with his clients Florence Lassandro and Emilio Picariello received full dramatic treatment in the Canadian opera “Filumena”. Staged by Calgary Opera, it is one of only a small number of Grand Operas to be written and produced in Canada.)