Stacy F. Kaufeld, M.A.

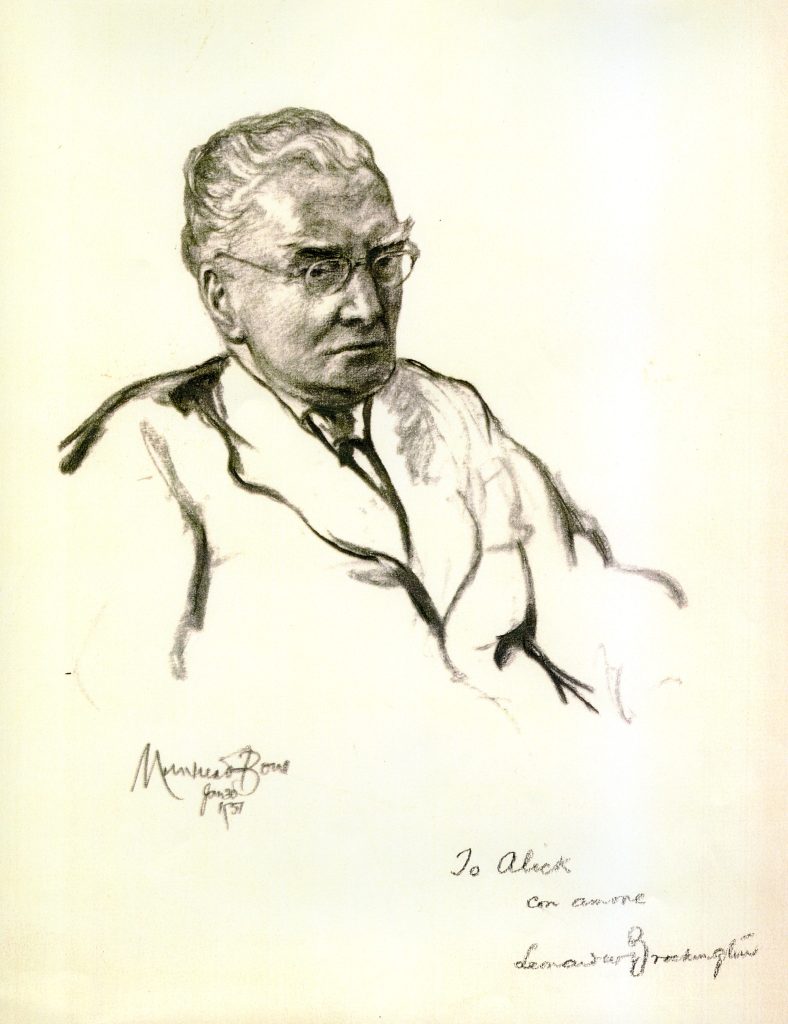

Throughout his legal career, Calgary lawyer and World War II veteran, Edward M. Bredin, Q.C., formed a deep interest in the life and career of another Calgary lawyer, Leonard W. Brockington. Brockington, or ‘Brock’ as he was affectionately known to his friends, practiced law in Calgary with R.B. Bennett, as well as being City Solicitor from 1922 to 1935. Bredin, himself a City Solicitor, likely came across Brock during the course of his own work at the City of Calgary and became enamoured with the enigmatic figure. The more Bredin delved into Brockington’s life and career the more be realized this former Calgary City Solicitor was a great national and international renown

The following post is largely based on writings authored by Ed Bredin about Brockington.

Brockington was born in Cardiff, Wales on April 6, 1888. At the age of fifteen, he received his senior certificate from the Cardiff Intermediate School for Boys and was awarded a scholarship to the University of South Wales. At university he was head of the debating society, the drama society, and was Editor of the school newspaper. He received his Bachelor of Arts degree magna cum laude with honours in Latin and Greek in November 1908. After graduating he taught English, Latin, and Greek at Cowley Grammar School in St. Helens Lancashire until 1912 when he emigrated to Canada.

LASA Accession 2009-004

He later recalled in a speech in Charlottetown in 1964, “I had never met a Canadian in my life, as far as I have known, I had never seen one.”[1] Armed with letters of introduction to the Moncton editor and the Principal at McGill University, Brock set sail for the new world. He remembered changing his destination when he heard an Irishman, who he had met on the ship, was headed to Edmonton. Brock said of his journey westward:

“I proceeded westward to a town (the name of which I had never heard before) on a colonist car, in company with the most outlandish people I have ever seen: Most of the men were wearing sheepskin coats, and the women had shawls over their heads, and they spoke no English. They come from places of which one never hears any more: Galicia and Ruthenia.”[2]

Arriving in Edmonton during the winter, Brock quickly realized that he was, in fact, dressed as the outlier, and the European immigrants were far better prepared for the harsh winter conditions of Alberta.

Brock initially found a job at a law firm in Edmonton. A great opportunity for someone who wanted to become a lawyer but lacked the requisite degree to practice in Alberta. However, the job was unpaid making it difficult to afford law school and to live in Edmonton. He found paid work with the Strathcona Plain Dealer, which indirectly led to his admission to law school at the University of Alberta as a part-time student. After the Plain Dealer closed and while enrolled at law school, Brock became Assistant Secretary to the City Commissioner at the City of Edmonton, as well as becoming editor of the City’s official gazette.

He married his wife, Agnes Neaves Mackenzie, on May 31, 1913. Though he was making less that one hundred dollars a month he was able to rent a small home in Edmonton. His quaint life was suddenly upended on Christmas Eve 1914. After making a speech supporting a city Alderman who happened to be a political rival of Edmonton Mayor, William Thomas Henry, Brock was fired. Brock demanded to know why he was being fired. “Economy” replied the mayor. “Financial or political?” Brock asked. “Take your pick” said the mayor, “[y]ou’re fired in either case.”[3] Though still in law school but with limited job prospects in the provincial capital, Brock moved to Calgary with hopes for a better future.

Later in Ottawa, Brock recalled in a conversation with Fred Kennedy, author of Alberta was my Beat: “Memoirs of a Western Newspaperman”, that he arrived in Calgary nearly destitute with his companion, Christmas T. Jones. They were lucky enough to find free room and board until they found jobs. Being similar in size both men shared one suit and alternated looking for employment.[4] Brock found a job in the Calgary Land Titles Office, which secured important contacts in the legal community, and he was also a school trustee. He remained enrolled at the University of Alberta without having to attend lectures. He completed all his necessary university exams and wrote his First Intermediate Examination in May 1916 receiving high marks.

On December 15, 1916, Brock started his three years of articles with Calgary lawyer, Louis Melville Roberts, at the city’s largest firm, Lougheed & Bennett. He was admitted to the Law Society of Alberta on January 3, 1920, and continued to practice at the firm. Considered a capable lawyer and performing the work of a typical junior, he was not paid well. It would be a tremendous understatement to describe Bennett and Brock as opposites. Bennett was introverted and considered the law and politics as hobbies. Whereas Brock was an extrovert enjoying several activities outside the law, especially athletics and the arts. Moreover, Bennett did not share Brock’s sense of humour.

As an articling student at the time, the Honourable E.R. Tavender recalled a time when Brock arrived at the office at nine o’clock in the morning and Bennett discovered him sneaking up the back stairs. Tavender remembered Bennett saying, “young man, don’t you know that this office opens at eight?” “I know,” responded Brock, “but I was told I could have one month’s holiday this year and I am taking it one hour each day.” Bennett was apparently not amused with Brock’s attempt at humour.[5]

Brockington left the firm on January 1, 1921, before the famous split between Bennett and Lougheed. He took a position with the City of Calgary as Assistant City Solicitor working under Clinton J. Ford, later Chief Justice of Alberta. He also partnered with Alderman Fred Shouldice to establish a firm Shouldice Brockington & Boyd in 1922, which became Shouldice Brockington & Price in 1924. The firm opened its office in what was then the Canada Life Building, later the Hollingsworth Building, and is currently a part of Bankers Hall. Brock maintained his practice with Shouldice after being promoted to City Solicitor on January 1, 1922. It seems possible that the City Solicitor’s Office was demanding more of Brock’s time and he left the firm in 1924. But more likely it was the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis that caused him tremendous pain and limited his mobility.

His work at the city rarely took him to court, but his primary role was advising the mayor, the commissioners, and various council committees. There was certainly no lack of work at the City of Calgary during the early years of the Great Depression. It was through his competence as a lawyer and his connections to learned people in the profession that Brock was able to stir the city through its foreign exchange crisis in 1932. At the time, the Canadian dollar was at a discount of about twenty percent with the American dollar. Interest in the city’s funded indebtedness was payable only in US dollars. The city refused to pay the exchange on the interest then due. The bondholder, represented by Calgary lawyer A.L. Smith, sued the City of Calgary. Brock, on the advice of Dean John A. Weir from the University of Alberta and Marshall Porter, asked Prime Minister Bennett to release enough gold from the federal government’s reserves to cover the exchange on the interest payment.[6]

On August 29, 1929, Brockington introduced Winston Churchill at a luncheon at the Palliser Hotel. In recognition of Churchill’s popularity, the city aimed to maximize attendance by charging only five dollars for the lunch. The event attracted more guests than the Crystal Ballroom at the Palliser could accommodate, resulting in many attendees having to dine outside near the building to hear the speeches. Churchill expressed interest in Turner Valley, noted at the time as the greatest oil field in the British Empire, and requested a tour. Brock accompanied Churchill and his guests in a 1925 Lincoln provided by Senator Pat Burns. Following Churchill’s death, Brock reflected on the evening spent with him at the Prince of Wales Ranch in a full-page tribute in the Globe and Mail. He recalled surprising Churchill by mentioning he had read all of his books and remarked, “[e]ven the greatest of authors and the greatest of men are not displeased with a little knowledge of their written words shown by an obscure man from the backwoods.” [7]

It was because of his legal career that Brock became a well-sought-after speaker. He had given a number of speeches, but it is widely believed that his 1932 speech at the St. Laurent dinner was his “big break”. He gracefully acknowledged CBA President and future Prime Minister of Canada, Louis St. Laurent. The speech, albeit short, was filled with Brockington humor. Brock, like many of his contemporaries, had a high respect for the legal abilities of Prime Minister, R.B. Bennett, who was in attendance. However, Brock did not like Bennett’s single-minded attention to business and his ascetic lifestyle. He told his audience:

[Bennett] is here on holiday. But let nobody be misled. The Prime Minister’s idea of a holiday is to read a parliamentary bluebook while he is shaving and sing the swan-song of Free Trade in his matutinal bathtub.[8]

This speech was significant because Brock became life-long friends with St. Laurent, and he was also invited to give the keynote address the Canadian Bar Association annual dinner in Ottawa in 1933 where he met Prime Minister W.L. Mackenzie King.

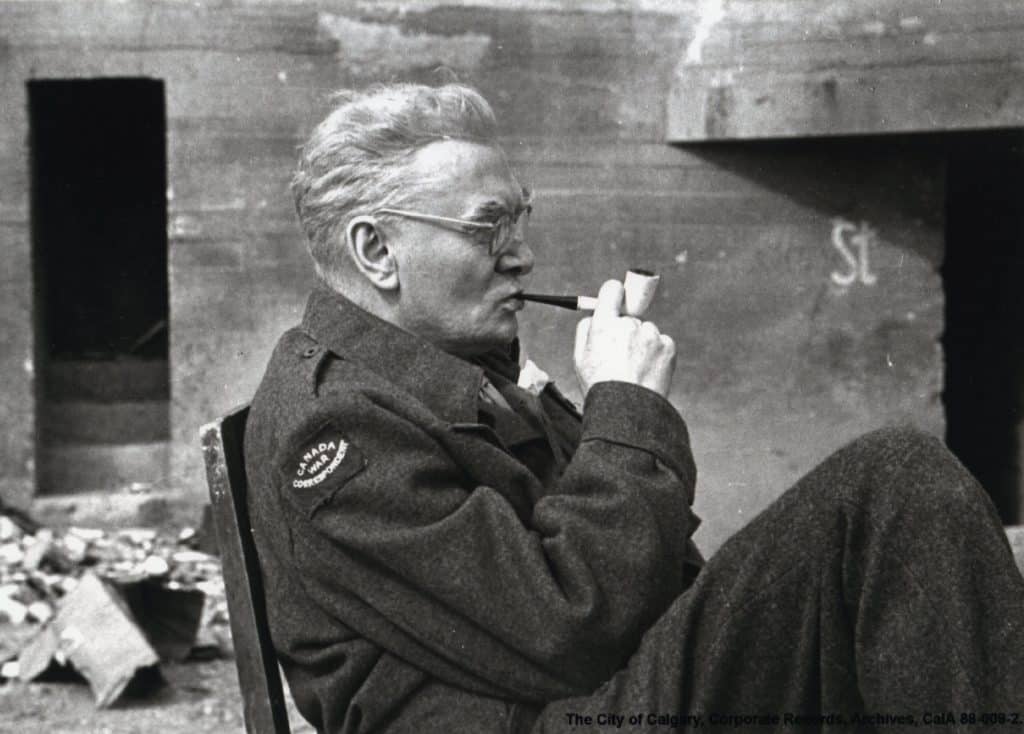

In 1935, Brock resigned as City Solicitor to take a position as general counsel with the newly established Northwest Grain Dealers Association in Winnipeg. He also went on to become the first Chairman of the Canadian Broadcast Corporation in 1936. After World War II broke out, he was appointed Recorder of Canada’s War Effort. A largely undefined position but led the way to his appointment in England as advisor on Empire Affairs to Brendan Bracken, the Minister of Information under Winston Churchill. Before the war’s end, Brock was on board the Canadian Destroyer Sioux from which he observed the D-Day landings on June 6, 1944.

He returned to Canada where he took several advisory positions with the government, he became Rector at Queen’s University and appointed to the Board of the Canadian Council. Brock continued to enjoy delivering speeches. In addition to his after-dinner appearances, he paid tribute to Gandhi, King George VI upon his death in 1952, as well as Winston Churchill after he passed away in 1965. Leonard Brockington passed away at the age of 79 on September 15, 1966, at his home in Toronto, Ontario.

[1] Cited in Edward M. Bredin, 2015, “Leonard Brockington: A Life,” Occasional Paper Series, Legal Archives Society of Alberta, pg. 13. https://legalarchives.ca/occasionalpapers/Leonard-Brockington_A_Life.pdf

[2] Cited in Ibid., pg. 14.

[3] Ibid., pg. 17.

[4] Cited in ibid., pg, 18 and Fred Kennedy, Alberta Was My Beat: “Memoirs of a Western Newspaperman” (Calgary: The Albertan, 1975), pg. 341.

[5] Bredin, “Leonard Brockington: A Life,” pg. 20.

[6] Edward M. Bredin, “Calgary’s Silver Tongued City Solicitor: Leonard W. Brockington C.M.G. LL.D D.C.L. K.C.,” in Citymakers: Calgarians after the Frontier ed. by Max Foran and Sheilagh Jameson (Calgary: The Historical Society of Alberta, Chinook Country Chapter, 1987), pg. 89-90. For more on Calgary’s foreign exchange crisis see Edward M. Bredin, “Calgary’s Foreign Exchange Crisis of 1933,” Alberta History 57, no. 3 (Summer 2008): pg. 8-13.

[7] Globe and Mail, January 26, 1965, pg. B16.

[8] Cited in Edward M. Bredin, “Leonard Brockington: Calgary’s Silver-Tongued Orator,” Alberta History 56, no. 1 (Winter 2008): pg. 24