By Stacy F. Kaufeld, M.A.

LASA hosted its first Annual Historical Dinner in two and a half years in Medicine Hat, Alberta, at the Medalta in the Historic Clay District on Thursday, June 2, 2022. We were delighted to welcome the Honourable Russell Brown, Justice of the Supreme Court of Canada, who spoke about Medicine Hat’s historical connections to Canada’s top court.

The road to this dinner is a story in itself. As Justice Dallas K. Miller once quipped in early 2021, “this is likely the most discussed dinner that has never taken place in LASA’s history.” He is not wrong. Let us venture back to 2019, before anyone had heard of Coronavirus or Wuhan, China, and well before lockdowns, quarantine, and masks became part of our everyday lexicon. Justice Miller approached LASA Chair, Shaun T. MacIsaac and myself about celebrating the centenary of Alberta’s oldest, still active courthouse in Medicine Hat.

LASA had worked with the Medicine Hat Bench and Bar in the past to promote a short movie, The Agreement, featuring local lawyer, George T. Davidson, who volunteered for King and Country at the outbreak of hostilities in Europe in 1914. The short film was based on the transcript of the Medicine Hat Bar Association’s send-off soiree for the young lawyer. Spoiler Alert: Davidson died at the Battle of the Somme in 1916 and did not return home. LASA, working with an excellent group of Medicine Hat lawyers, premiered the film at the Monarch Theatre in the historic downtown on June 16, 2016, followed by a wonderful dinner with the Medicine Hat Bench and Bar.

When Justice Miller approached LASA with his idea, it seemed like a ‘no-brainer’. Celebrating a historic Alberta courthouse and a chance to once again collaborate with the wonderful members of the Medicine Hat Bench and Bar. A date was set, September 24, 2020, a venue was chosen, the Medalta, and an invitation was extended to Justice Brown who graciously accepted. As they say, the wheels were in motion.

But wait…March 2020.

On March 17, 2020, the Alberta government declared a public health emergency. After many discussions and given the plenty of unknowns, LASA made the difficult decision (though the limits placed on public gatherings made the decision for us) to postpone the dinner. However, LASA was fortunate enough to participate in a physically safe, socially distanced event commemorating the one hundredth anniversary of the opening of the courthouse on September 24, 2020, where the Medicine Hat Historic Society unveiled a plaque to celebrate the history of the Courthouse. Former MLA and Alberta Minister of Justice, the Honourable James D. Horsman, recalled efforts to save the building from demolition starting in the 1960s, and while in cabinet he was able to ensure its preservation to include a modern extension on the back.

Planning continued and as things related to COVID-19 seemed to be fading into the early summer of 2021, LASA rescheduled the dinner for September 23, 2021, at the Medalta in Medicine Hat with Justice Brown as the guest speaker. Unlike the previous year, this time we made a formal announcement and began selling tickets. Confident, though the number of COVID cases was rising over the summer, that we would be able to host the event before any restrictions on public gatherings were reinstated.

But wait…the fourth wave.

On September 15, 2021, the Alberta government announced the return of restrictions on public gatherings effective September 16, one week before the scheduled event. Once again, LASA postponed the dinner.

In early 2022, Justice Miller, Shaun T. MacIsaac, and I discussed one last attempt to host the dinner. We set the date, June 2, 2022, booked the Medalta, and confirmed Justice Brown would be available to finally deliver the speech he had written two years earlier. Despite a pandemic and two postponements, LASA, along with the Medicine Hat Bench and Bar, was finally able to successfully commemorate what became the 101.75th anniversary of Alberta’s oldest, still active courthouse with lawyers and judges from Medicine Hat, Brooks, Lethbridge, Calgary, Red Deer, and Edmonton, along with a few of the interested public. As the saying goes, third time’s the charm.

Justice Russell Brown was born in Vancouver on September 15, 1965. He received a Bachelor of Laws from the University of Victoria in 1994, as well as a Master of Laws in 2003 and a Doctoral of Juridical Science in 2006, both from the University of Toronto.

Justice Russell Brown was born in Vancouver on September 15, 1965. He received a Bachelor of Laws from the University of Victoria in 1994, as well as a Master of Laws in 2003 and a Doctoral of Juridical Science in 2006, both from the University of Toronto.

From 2004 to 2013, Justice Brown was a member of the Faculty of Law at the University of Alberta. His principal areas of interest were commercial law, medical negligence, public authority liability, insurance law, and trusts and estates.

From February 8, 2013 to March 7, 2014, he sat on the Court of Queen’s Bench of Alberta, after which he was appointed to the Court of Appeal of Alberta. He became a Justice of the Supreme Court of Canada on August 31, 2015.

A prolific writer, Justice Brown has authored books on negligence law for economic loss, he contributed to textbooks on public authority liability, and has published over 40 law review articles, book chapters, and essays on tort law, property law, and civil justice. In addition to his judicial duties, Justice Brown currently serves on the editorial board of the University of Toronto Law Journal and the advisory board of the Legal Writing Academy at the University of Ottawa.

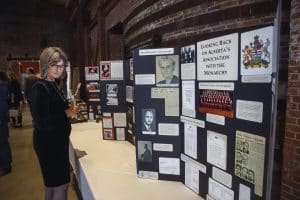

Following a wonderful introduction by two former students, Leslie Stitt and Kerry Gellrich, Justice Brown took to the stage to recount the deeply entrenched legal history of Medicine Hat. He spoke about a number of cases, many of which originated in the very courthouse we were assembled to commemorate, that were eventually decided at the Supreme Court of Canada.

Medicine Hat has quite an interesting legal heritage. Justice Brown told the audience his knowledge of this history began when he peer reviewed a manuscript of William Kaplan’s biography of Ivan Rand. Rand was a judge on the Supreme Court of Canada from 1943 until 1959, and Justice Brown suggested that he is “possibly the greatest judge, and easily among the greatest two or three judges in the court’s history.” As an early connection to Canada’s top court, Justice Rand began his career in Medicine Hat in 1912 after receiving his law degree from Harvard. He practiced with the firm of Laidlaw, Blanchard and Rand (now Pritchard & Company LLP) until 1920.

The speech was a perfect mixture of law and history and tied the development of the law in southern Alberta to the economic and social context of the times. As the region was experiencing an economic boom and the population grew, things became relatively more litigious, and lawyers and the courts were needed to settle disagreements. As Justice Brown explains, it was the promise of economic prosperity that brought Medicine Hat’s first case in 1914, Roots v. Carey, to the Supreme Court of Canada where the Court dealt with the legal principle of ‘offer and acceptance’.

Mr. Roots and Major A.B. Carey entered into an agreement over a quarter section of land on November 26, 1910. Major Carey sent Mr. Roots a letter on January 26, 1911, with modifications to the original terms of the agreement. When Major Carey received no response, he tendered payment for the land. When the land was not conveyed, Major Carey sued Mr. Roots. The question before the Court, Justice Brown identified, had to deal with whether a contract existed between the two parties. Chief Justice Fitzpatrick, and Justices Idington and Duff concluded that the modifications in the January 26 letter were indicative of a counteroffer, which required Mr. Roots explicit acceptance. However, Justice Anglin and Davies argued that the January 26 letter was a clear acceptance of the offer, the slight modification in the transaction notwithstanding.

Reflective of the appeal for land in Medicine Hat, Justice Brown suggests that Mr. Roots failed to respond to Major Carey’s letter because “he had already conveyed the land a month earlier to one Mr. Brown for 25% more than the terms he had proposed to Major Carey.”

Prior to World War I, Medicine Hat was booming. Optimism and, yes, land speculation were on the rise. The Medicine Hat News opined that “Medicine Hat will shortly take its place amongst the greatest and possibly largest cities in the North American Continent.” Sitting on a large field of natural gas, the city was glowing with expectation, which attracted new business, building of schools, the prospect of CPR building a maintenance facility, and the construction of a water treatment plant to provide clean water to the presumed population of 50,000 in the years to come.

By the time the Supreme Court heard the case in 1914, Medicine Hat’s optimism started turning to pessimism. Fighting was raging in Europe, the CPR preferred Calgary to build its maintenance facility, and the real estate market began feeling the economic effects and prices fell. What was a city with a population of 15,000 in 1913 decreased to 9,000 by 1915. With these changing circumstances, Justice Brown suggested, Major Carey likely felt relieved despite his loss in Ottawa.

As the situation continued to worsen, the need for the courts grew. Justice Brown told the audience “the turn in Medicine Hat’s fortunes occupied so much the Supreme Court’s attention.” He detailed a number of cases where the main issue at the Supreme Court was to get out of land purchase agreements.

One such case was Bowlen v. Canada Permanent Trust Co., where Mr. Bowlen, a rancher near Cochrane, Alberta, entered into an agreement in 1913 with Mr. Healy to purchase one-quarter interest in some building lots in Medicine Hat. Mr. Bowlen argued that he paid the purchase price but received no land conveyance and had since renounced the agreement. At the Supreme Court of Canada, he wanted repayment with interest, an amount far beyond the land’s 1914-1915 value. The judges unanimously determined that Mr. Bowlen had not entered into an agreement for title of the land, but entered into a joint venture whereby his interest in the land would grant him right to a portion of the profits. In other words, as Justice Brown reasons, “Bowlen could not now recoup his losses by reframing the agreement as one of sale.”

In the post-World War II period, Medicine Hat experienced a return of its good fortunes as reflected in the Supreme Court’s 1958 judgement in Midcon Oil & Gas Co. v. New British Dominion Oil Co. Justice Brown asserts this case is a “success” story about “how the West’s first phosphate fertilizer manufacture, Northwest Nitro Chemicals Ltd., came to be.” In 1951, the two parties entered into an agreement allowing Midcon to drill and test in Etzikom Field, owned by New British Dominion Oil, outside Medicine Hat. Once Midcon drilled to a specified depth, New British agreed to transfer to Midcon a “undivided one-half interest” in the rights and future developments.

As it turned out, the Etzikom Field was sitting on a large reservoir of gas. After a number of proposals were put forth, including getting the gas to market, New British entered into an agreement with Consolidated Mining and Smelting to build a chemical fertilizer plant in southern Alberta. Estimates suggested that the $22 million facility built in 1954 would utilize nearly half the field’s gas, while an agreement was struck between Consolidated Mining, incorporated as Northwest Nitro, and City of Medicine Hat for the remainder of the gas. The deal between Northwest Nitro and New British saw the latter receive one-third of its preferred shares, and under one-third of its common shares.

The issue at the Supreme Court, Justice Brown maintains, was not about the supply agreements. Rather, Midcon took issue with how New British obtained their shares in Northwest Nitro and sought a judicial order necessitating New British to sell half of those shares to Midcon. For the majority, Justie Locke wrote, “I know of no principle, either of law or equity, which in these circumstances restricted in any manner the liberty of the respondent to take part in the promotion of a company and to acquire shares in that company, in the hope that it might become a possible purchaser of the gas.” Justice Rand, writing for the dissent argued that New British could not profit from this dealing given its status as a fiduciary. He wrote, “[e]quity by an absolute interdiction…puts temptation beyond the reach of the fiduciary by appropriating its fruits.”

As Justice Brown suggests, one might be forgiven, when listening to his speech, to conclude that all legal actions coming out of Medicine Hat were related to “business – about contracts, commercial law and tax law.” He continues, “[b]ut that changed while I was under COVID lockdown reading these cases and trying to find something that would hold the attention of a diverse audience. For it was then that I stumbled across a real gift.” If there is to be a silver-lining in two dinner postponements, arguably it could be giving Justice Brown time to uncover this case.

The case involved G.M. Goddard and his “special friendship” with J. Crittenden. Mr. Goddard was a widower in his eighties who never had biological children with his wife, but had adopted their nephew, the plaintiff Mr. Bradley, when he was three years old. After moving to Medicine Hat from Newfoundland in 1918, Mr. Goddard bought Mr. Bradley, whom he treated like a son, a farm outside Medicine Hat and a house in town. Following his wife’s death in 1923, he began befriending Mrs. Crittenden, who was separated from her husband and thirty-fives younger. Their relationship developed beyond friendship as they were seen “kissing” and purchased property – in her name only – together. Mr. Goddard proposed marriage six times in three years.

In the wake of his wife’s death, Mr. Goddard had a will drawn up in 1924 leaving his entire estate, including forty-four shares in the Bank of Nova Scotia, to Mr. Bradley. At this point, Mr. Goddard’s mind and body were beginning to fail him. Mrs. Crittenden queried a local solicitor about the validity of holograph wills. In 1929, a holograph will appointed her executor and she also received the bank shares. In 1930, a second holograph will was drawn up and Mr. Bradley was reappointed executor and sole beneficiary of his father’s estate. However, it was too late, Mr. Goddard had already transferred the shares to Mrs. Crittenden.

In the wake of his wife’s death, Mr. Goddard had a will drawn up in 1924 leaving his entire estate, including forty-four shares in the Bank of Nova Scotia, to Mr. Bradley. At this point, Mr. Goddard’s mind and body were beginning to fail him. Mrs. Crittenden queried a local solicitor about the validity of holograph wills. In 1929, a holograph will appointed her executor and she also received the bank shares. In 1930, a second holograph will was drawn up and Mr. Bradley was reappointed executor and sole beneficiary of his father’s estate. However, it was too late, Mr. Goddard had already transferred the shares to Mrs. Crittenden.

Mr. Goddard died in 1931, at which time Mr. Bradley challenged the validity of the shares by alleging “incapacity and undue influence.” The trial judge, Justice A.F. Ewing, agreed that the transfer of shares was “brought about by undue influence exercised by a younger woman on the failing mind and generous heart of the old man.” The Court of Appeal reversed the decision reasoning Mrs. Crittenden “held no more influence over him than a friend.” A divided Supreme Court dismissed the appeal on similar grounds that unrequited love is not a presumption of undue influence. Justice Brown concluded that this Medicine Hat case made “an important contribution to Canadian testamentary law.”

Justice Brown concluded his remarks asserting Medicine Hat was the quintessence of the entrepreneurial spirit of Western Canada, a city of “commercially-minded people, people who wished to build something…notorious for the civic pride and determined that their communities should hold a prominent place in a nation. Even during economic difficulties that drive to build never waned. “Law is the product of the places and times in which it is made,” he argued. These cases represented the embodiment of a hardworking and resourceful character of the citizens of Medicine Hat.

The Legal Archives Society of Alberta wishes to thank all those who attended this wonderful evening and who continue to support our work to preserve and promote Alberta’s legal heritage. LASA wishes to thank all the organizers of the event, especially Justice Dallas K. Miller, as well as the evening’s speakers who helped make this a memorable evening. LASA wishes to thank the Honourable Russell Brown, who accepted our invitation.