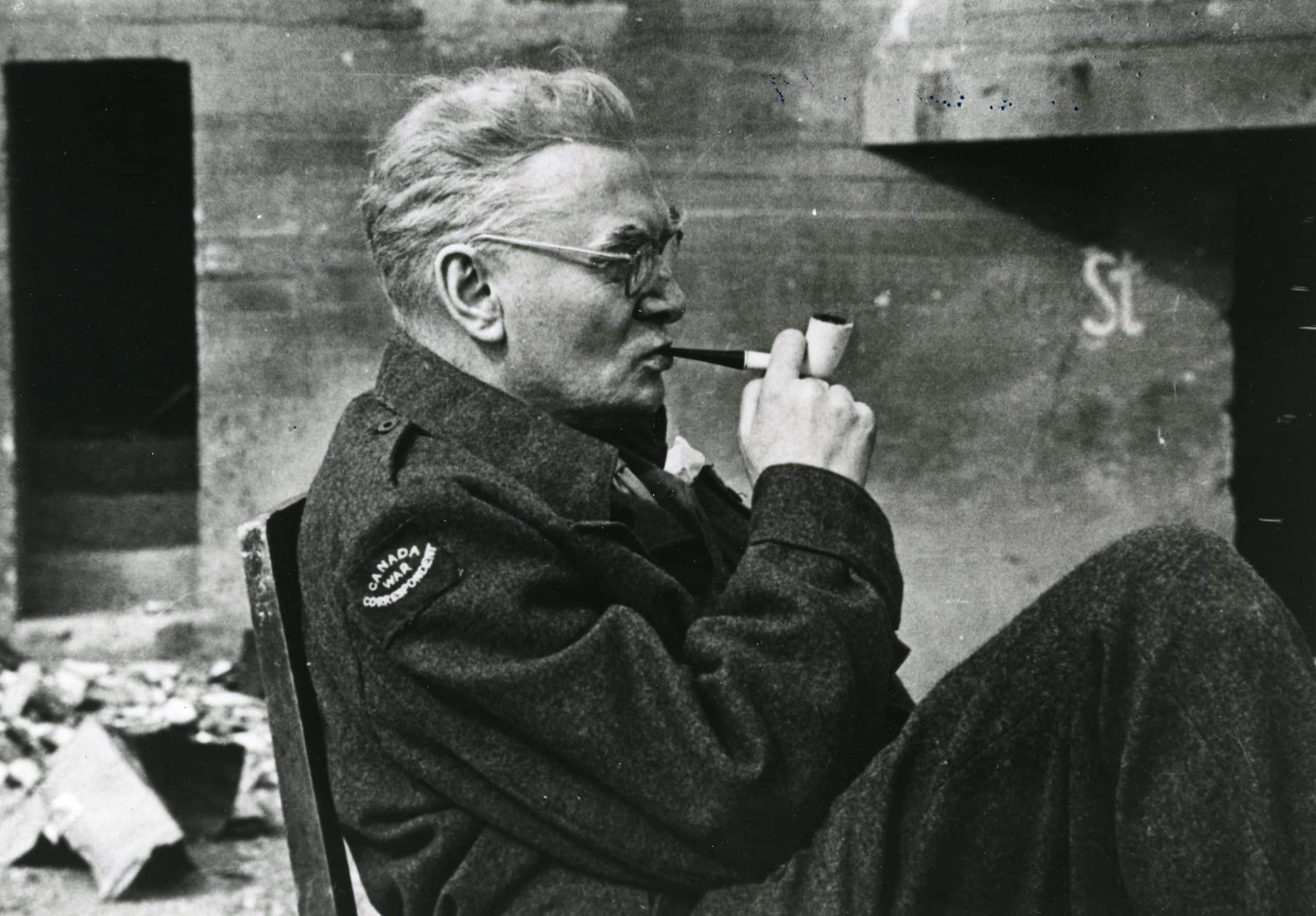

On June 6, 1944, men from Allied nations fighting Nazi tyranny made a harrowing trip across the English Channel to the beaches of Normandy. Leonard Brockington, a Calgary lawyer, was reporting for CBC Radio about the invasion of Europe from the Canadian Destroyer Sioux. The following is an excerpt from the biography of Brockington written by fellow Calgary Lawyer, Edward M. Bredin, Q.C.

Arguably, one of Brockington’s greatest moments during the Second World War was joining the Canadian Destroyer Sioux from which he observed the D-Day landings on June 6, 1944. In his speech to the American Bar Association, Brock recalled that the armada across the English Channel was “the best example of the union of hearts and minds of two nations that it ever will see, the invasion fleet that set out to reach the coast of France on the morning of the great D-day.”

Arguably, one of Brockington’s greatest moments during the Second World War was joining the Canadian Destroyer Sioux from which he observed the D-Day landings on June 6, 1944. In his speech to the American Bar Association, Brock recalled that the armada across the English Channel was “the best example of the union of hearts and minds of two nations that it ever will see, the invasion fleet that set out to reach the coast of France on the morning of the great D-day.”

Given the lack of radio statistics and demographics from the period, it can only be surmised that the radio audience for the D-Day landing was likely Brockington’s largest. Although not broadcast on the CBC until June 18, 1944, Brock managed to give the Canadian public a first-hand account of “history in the making”. The program had all of the makings of a great Brockington speech. Humor and wit mixed with facts and prognostication about what this invasion would mean for the subsequent course of the war and future. Despite being transmitted twelve days after the invasion, Brockington’s broadcast from aboard the Canadian Destroyer painted such a picture that listeners felt as if they were there crossing the Channel.

Brockington told his CBC audience that Operation Overlord (D-Day’s official name) was, “a story of skill and forethought, devotion, resolution, preparedness, courage and overwhelming might unequalled in the annals of warfare.”

Imagine what Brockington must have witnessed while on board a ship that was among many taking the first major steps towards liberating Europe from Hitler’s Germany. Imagine having listened to him retelling his experience with eloquence and passion that only Brock could have done. During his broadcast, he painted a picture for the audience describing what he experienced while on the Sioux.

Brockington quoted a British Admiral who was giving this latest armada a little historical context before crossing the English Channel. The Admiral stated, “[w]hat Philip of Spain tried to do and failed; what Napoleon wanted to do and could not; what Hitler never had the courage to attempt, we are about to do, and with God’s grace we shall succeed.” In this sense, history was certainly not on the Allies’ side. However, those were all attempts or planned attempts to invade England across the Channel. Although Operation Overlord was arguably the most well planned invasion in history, it could be surmised that crossing the Channel in the other direction this time would be a source of fortune.

Once Brockington arrived at the port from which he would depart, he described the scene of which he opined, “can never be forgotten.” He detailed, “[t]housands of ships of all shapes and sizes and uses – British, American, Canadian, Polish, French, Norwegian, Dutch – battleships, cruisers, destroyers, landing craft, frigates, monitors, corvettes, freighters carrying strange cargoes, tankers, mystery ships hidden by acres of tarpaulin, all rode serenely at anchor unthreatened by the enemy that once used to sing that he was sailing against England.”

Brockington was to embark on a journey of which no one – not even the greatest military minds – could predict the outcome, but were genuinely optimistic for success. He was able to maintain his wit and humour. When asked what the enemy would do with him if captured, he replied, “[h]e will take my picture…and put me on every newsreel and photo service. Underneath he will write – ‘If you want to know the depths to which the British Empire has sunk, look at this typical Canadian soldier’.” He likely had known that the chances of being captured by the enemy was minimal, he would more likely have drowned or been fatally wounded during the crossing. He also likely could foresee that many of the young men who were crossing the Channel were not going to survive. He used his humour to maintain the good-natured attitude, though every person in that port knew what dangers laid ahead.

Brockington recalled a conversation he had with a Captain the Saturday prior to D-Day. They discussed their particular objective – Juno Beach – their strategy, what the pre-raid bombing the immediate night before D-Day would accomplish for those crossing on June 6. The initial date for the invasion of the continent was Monday, June 5. However, the weather did not cooperate, and the invasion was delayed until the next day. However, the weather had only slightly improved. Of the weather and its effect on the mission’s strategic outcome, Brock simply stated, “not…all to our disadvantage.”

Brockington listed minute-by-minute the initial approach to France. Without recalling in great detail all this action, it is worth noting some of the language that created the imagery for his listeners. Here are just a few of the more poignant examples, “At 5.30 [sic] it was daylight and what a sight met our gaze. A great semi-circle of hundreds of ships lay off the enemy’s coast.” Brock continued, “[t]hunder answered thunder, tanks went ashore; guns went ashore; men went ashore; fires broke out; the coast was enveloped in smoke… .”

Lastly Brock spoke about the brave, young soldiers, “I never expect my heart to throb at a more thrilling sight of men going gaily to the unknown than of those Canadian soldiers on those landing barges. I saw dozens of ratings gazing with fascinated eyes and saying ‘Look – our boys’.”

Upon concluding his broadcast, he thoughtfully evoked what this invasion meant for the people of Europe and for the future of humanity. In recounting a conversation that called to mind historical imagery with the Chief Engineer aboard the Sioux on the evening of June 6, 1944, Brock declared, “many fleets of ships have crossed these waters to bring destruction to innocent people and slavery to the free.” He continued, “[t]his armada is different. It is the first that ever set out to bring freedom to all men.” To which the Chief replied, “and that’s what makes everybody feel good – and every Canadian glad to be here.”

Brockington essentially became what is known today as an embedded reporter. Certainly, his intent was to relay to his Canadian audience the first-class involvement of the Canadian forces in fighting the war. Brockington would likely argue that Canadians, regardless of background, should be tremendously proud. Although it is difficult to measure what affect these speeches had on audiences, listeners and citizens, it is clear from the emphasis placed on their contribution that the leaders – civilian and military – believed they worked. Hutton quoted the response from Brock’s Australian audiences, “[his speeches] revealed a technique entirely new to Australia…an episodic method of drawing on a rich store of experience, spiced with humour.”

Photo Courtesy of City of Calgary, Corporate Records, CalA 88-009-2