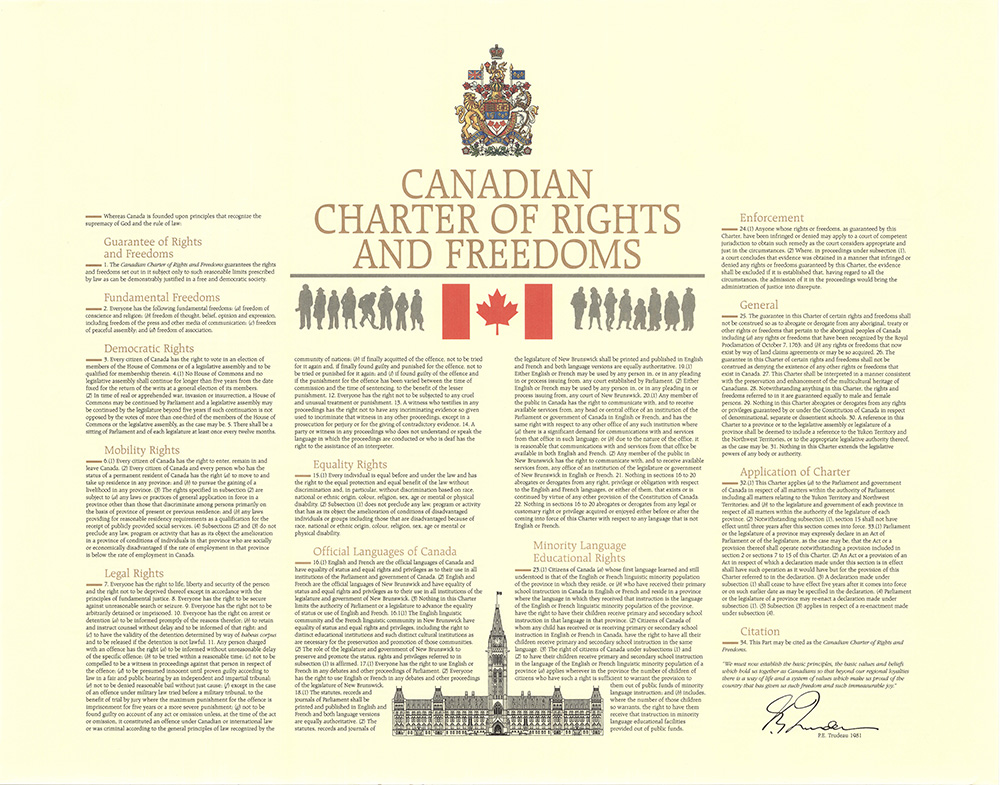

On April 17, 2022, the fortieth anniversary of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms has come and gone. Since its introduction, there has been plenty of discussion about the political and legal significance of the Charter over the last forty years. Forty years is not a long time. In fact, it amounts to approximately one quarter of Canada’s 155-year existence. It is almost impossible to divorce the Charter’s political and legal importance from its historic context. After all it is a legal document that protects individual rights and freedoms from breaches by the federal and provincial governments. Because it was combined with the Patriation of the Constitution coupled with a made-in-Canada amending formula granting Canada sovereign independence from the United Kingdom, the Charter is also a political document. The historical significance can be viewed through the Charter as a foundation of Canadian identity, as well as its strengthening of democracy, and the social values and moral obligations it symbolizes.

As will hopefully become clear, law and society are not mutually exclusive. They work together. The Charter has deeply shaped the law since 1982 and it has equally influenced Canadian society. Like the legal system in general, many Canadians have a facile grasp of the Charter. Often they only give it serious thought when a specific right has been violated. Such an approach fails to acknowledge how it informs everyday life. Michael Ignatieff argues that Canadians should not “underestimate the importance of ‘mere legal documents’ as the embodiment and crystallization of a demand for social change.”[1]

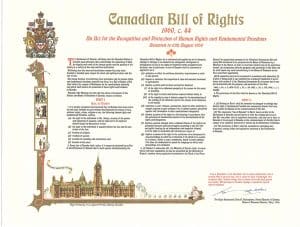

Why did Canada need a Charter of Rights and Freedoms? Considering Prime Minister John Diefenbaker introduced the Canadian Bill of Rights in 1960, which set out to accomplish many of the Charter’s objectives. Yet, there were a couple of key details missing in this first incarnation of rights protection. Whereas any federal government could repeal or amend the Bill of Rights, the Charter is entrenched as Part I of the Constitution and, therefore, can only be changed through a constitutional amendment. Further, the Bill of Rights did not apply to provincial legislation. The Charter protects fundamental rights and freedoms at both the federal and provincial levels of government. These two differences made it more robust than the Bill of Rights.

Why did Canada need a Charter of Rights and Freedoms? Considering Prime Minister John Diefenbaker introduced the Canadian Bill of Rights in 1960, which set out to accomplish many of the Charter’s objectives. Yet, there were a couple of key details missing in this first incarnation of rights protection. Whereas any federal government could repeal or amend the Bill of Rights, the Charter is entrenched as Part I of the Constitution and, therefore, can only be changed through a constitutional amendment. Further, the Bill of Rights did not apply to provincial legislation. The Charter protects fundamental rights and freedoms at both the federal and provincial levels of government. These two differences made it more robust than the Bill of Rights.

In the aftermath of World War II and the discovery of Nazi atrocities that swept across Europe, Western societies moved toward what Ignatieff called “the rights revolution” in the 1960s.[2] For Canada, the Charter of Rights and Freedoms represents the social values and moral obligations that reflect the maturity of a nation coming of age legally and politically. Those rights entrenched in a legal document expresses the will of the people, but also protect the rights of minorities against duly elected majorities. As Ignatieff suggests, “rights equality makes society more inclusive, and rights protection constrains government power.”[3] Because of the Charter, Canada is a more just society.

Initially many felt the Charter was a little ‘heavy-handed’. With the passage of time, it became clear that it was necessary for Canada’s future. Milt Harradence, former Justice of the Court of Appeal of Alberta, wrote in a speech given in 1991, “[W]hen one considers that today government is involved to an extent that was probably never contemplated by our forefathers in almost every aspect of day-to-day life, something more definite and more powerful is needed than the British North America Act or the Bill of Rights to preserve…fundamental freedoms.”[4]

The federal and provincial governments are duty bound to respect all the rights and freedoms enshrined in the Charter. Nevertheless, it is equally important to appreciate that rights are not absolute. With all rights come obligations and responsibilities, and one person’s rights are not more important than another’s. It seems that with the emphasis on individual rights there is fear that responsibility to society is being minimized. But this is not the fault of the Charter. Rather it is a failure to understand the importance of Section 1. There is a reason this is placed prominently at the beginning of the Charter and states that all rights and freedoms are guaranteed, but are “subject only to such reasonable limits prescribed by the law as can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society.”

For example, in the majority decision in R v Keegstra, the Supreme Court of Canada recognized that James Keegstra’s right to freedom of expression was violated when he taught antisemitism and Holocaust denial to his Alberta high school students throughout the late 1970s and early 1980s. But the majority also determined the violation was a reasonable limit in a free and democratic society. In other words, although section 2(b) guarantees freedom of expression, it comes with a responsibility not to hurt, defame, or cause other individuals or groups to be silenced.

A second reason for the emphasis of individual rights is the simple lack of respect for the rights of others. “There is always a danger with any entrenched bill of rights,” Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin observed, “that some people will attempt to use it to affirm their own rights while ignoring the responsibility to respect the rights of others.”[5] Freedom is not absolute. When one person’s rights trump their personal responsibility to others it minimizes accountability and citizenship in a democracy. Therefore, it is incumbent upon the courts to ensure that all rights and liberties for all citizens are respected.

Democracy, equality, respect, and dignity are all values that Canadians embrace. They are also principles that are engrained in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Notwithstanding the importance of the Charter as a legal document, it is equally a statement of these values and moral obligations. In a 2002 speech, McLachlin spoke of the Charter as a foundation of Canadian national identity. She suggested that the Charter reflects Canada as a nation in the present and into the future. Moreover, it is uniquely Canadian in its simultaneous respect for individual rights, as well as collective and group rights.[6] The document protects minority language rights and multicultural diversity, and also includes sections that entrench womens’ and Aboriginal rights.

Critics of the Charter argue that parliamentary supremacy is being usurped by judicial authority, and that it undermines democracy. They claim that judges are being unduly influenced by special interest groups whose value-ladened agenda is gaining traction over a strict interpretation of the law. As Ted Morton wrote, “the Charter has made the courtroom a new arena for the pursuit of politics.”[7] To believe that constitutional interpretation should be limited to “framer’s intent” or “original understanding” fails to recognize the social, economic, cultural, political, and legal developments in Canada. Furthermore, a strict reading of the British North American Act limits any analysis to the social and moral sensibilities of its authors. As McLachlin argued in 1991, “the Charter must not be viewed as a static document.”[8] Judges should not be so intransigent so as not to recognize the changing values of Canadians.

The Charter as a Living Tree

This idea is not new. The concept of the “living tree” interpretation of the constitution was first introduced into Canadian lexicon long before the establishment of the Charter. John Sankey, England’s Lord Chancellor, ruled on October 18, 1929, that women were eligible for a Senate appointment in Canada. In what is now famously known as the “Persons Case”, Sankey argued that Canada’s constitution is a “living tree capable of growth and expansion within its natural limits.” As such, he asserted, it “is in a continuous process of evolution,” and concluded that Canada required a “large and liberal interpretation” of the constitution to “meet the changing needs of Canadian society.”[9] The decision in the Persons Case long foreshadowed the role that courts would undertake in the post-Charter era. Reasonable individuals can disagree on which values best represent Canadians and how the courts maneuver around those constitutional interpretations. But social values and moral sensibilities have long played a role and will continue to be key in judicial interpretation.

The Role of Judges & the Notwithstanding Clause

The pre-Charter role of judges is now part of a bygone era. After 1982, judges began working with Parliament and provincial legislatures to ensure that rights and liberties are equal and protected. This new role for judges in the post-Charter era does not undermine democracy. On the contrary, it enhances and strengthens democratic values. Peter W. Hogg and Allison A. Bushell refer to it as “Dialogue”. It is not the courts dictating legislative ambitions. Rather, it is a communication between the courts and the respective legislative body to ensure that the objective of any legislation or law conforms with the Charter.[10] If corrective measures are taken following an adverse ruling to ensure that rights for all Canadians are respected while meeting the legislative imperative, it is hard to understand how judicial review weakens democracy. There is certainly no doubt that judicial review influences legislation, but evidence, as Hogg and Bushell reveal, fails to substantiate the concern that the Charter has led to a dictatorship of an unelected judiciary.

Even if the courts tread into the realm of politics, Parliament and the legislatures have one final option – Section 33, known as the “notwithstanding clause”. This section allows Parliament and the provincial legislatures to override sections of the Charter, in particular Section 2 and Sections 7 to 15. It declares an Act valid “notwithstanding” a specific section of the Charter. It is important to note that the use of Section 33 is subject to review after five years. The section was added specifically during the Patriation negotiations in order to appease the provincial governments to ensure elected bodies remain sovereign. Essentially, the overriding clause gave elected officials the final word on legislation over unelected judges.

The fears of value-laden judicial interpretation was really for not. As McLachlin argues, it is nearly impossible to “interpret the Charter without making value judgements.”[11] The courts and legislatures often follow society’s lead. Though the “notwithstanding clause” is meant to ensure that elected officials can override the courts, it has rarely been used. The federal government has never invoked Section 33. Quebec has invoked the clause fifteen of the approximately twenty times it has been used at the provincial level.[12] This is not because the opportunity is not there, but because the courts and the governing bodies have adapted to meet the necessary changes to society’s progress. As society is not static, neither is constitutional interpretation. As the study by Hogg and Bushell shows, Parliament and legislatures work with the courts’ suggestions to guarantee legislations follows the Charter.[13] Typically, the legislation is a reflection of that society.

Conclusion

As Canadian reflect on the Charter of Rights and Freedoms over the last forty years, there are only a few certainties. First, it is not perfect. In fact, it is the only bill of rights in an industrialized society that allows governments to override basic rights. Yet, this is something just and uniquely Canadian. Second, it is adaptable to reflect the social values and moral obligations of society, and has become a template for bills of rights internationally. Third, it unites Canadians. A recent Confederation of Tomorrow (COT) survey indicates overwhelming support for the Charter across a wide spectrum of demographics from sea-to-sea-to-sea. To paraphrase French historian Ernst Renan, a nation is fostered on commonly held ideas, history, and civic ideals. Because of the Charter Canada has grown as a nation since 1982.

[1] Michael Ignatieff, “The Charter at Thirty,” Osgoode Hall Law Journal 50 (2013): pg. i.

[2] Ibid., pg. ii.

[3] Michael Ignatieff, The Rights Revolution (Toronto: House of Anansi Press Limited, 2000), pg. 6.

[4] Transcript of a speech given to St. Mary’s High School, 5 December 1991, Asa Milton Harradence Fonds 115-00-04 vol. 30, file 127, Legal Archives Society of Alberta, Calgary, Alberta.

[5] Beverley McLachlin, “The Charter 25 Years Later: The Good, the Bad, and the Challenges,” Osgoode Hall Law Journal vol. 45, no. 2 (2007): pg. 375, https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/ohlj/vol45/iss2/4

[6] Beverley McLachlin, “Canadian Rights and Freedoms: 20 Years Under the Charter,” transcript of speech delivered in Ottawa, Ontario, April 17, 2002, https://www.scc-csc.ca/judges-juges/spe-dis/bm-2002-04-17-eng.aspx.

[7] F.L. Morton, “The Charter Revolution and the Court Party,” Osgoode Hall Law Journal vol. 30, no. 3 (1992): pg. 628. https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/ohlj/vol30/iss3/7.

[8] Beverley McLachlin, “The Charter: A New Role for the Judiciary,” Alberta Law Review vol. 29, no. 3 (1991): pg. 544.

[9] Quoted in Robert J. Sharpe and Patricia I. McMahon, The Persons Case: The Origins and Legacy of the Fight for Legal Personhood (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2007), pg. 6.

[10] Peter W. Hogg and Allison A. Bushell, “The Charter Dialogue Between Courts and Legislatures (Or Perhaps the Charter of Rights Isn’t Such a Bad Think After All),” Osgoode Hall Law Journal vol. 35, no. 1 (1997): pg. 80. https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/ohlj/vol35/iss1/2

[11] McLachlin, “The Charter,” pg. 542.

[12] Sean Fine, “Canada’s Charter turned 40 on Sunday – and it’s still as radical and enigmatic as it was in 1982,” Globe and Mail, April 17, 2022, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-canada-charter-turns-40-supreme-court/?utm_campaign=sophi-pop&utm_medium=post&utm_source=facebook&fbclid=IwAR3qg9t-f-M-m0VAtA9RoA-xf32AoCnaa503m6pWRl7G33re4Pjt0CIoON8 (accessed April 18, 2022).

[13] Hogg and Bushell, “The Charter Dialogue,” pg. 105.