The life and career of Arthur Gardner Lincoln was unlike most other Alberta lawyers who fought in World War I. Following a long and onerous process to become a lawyer – interrupted by war and coupled with a fair bit of ambiguity – it seems that Lincoln never actually practiced law in Alberta.

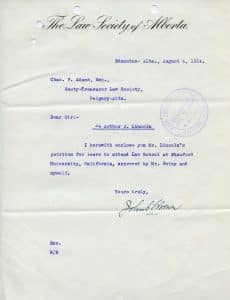

Born in 1886 in Stanstead, Quebec, there is little known about the early life of Lincoln. He came to Alberta after having lived in the United States where he attended law school at Stanford University in California. At the time he made his application to the Law Society on July 21, 1914, he was 28 years old. He indicated in the accompanying letter, that he intended to return to Stanford for a period of ten months between September 1, 1914 and July 1, 1915 to complete his studies. These plans were made while tensions in Europe were coming to a boil, but before hostilities broke out.

- B. Bennett, K.C., and Senator James Lougheed approved his application for a student-at-law position and the request to return to Stanford, in a letter dated July 29, 1914. One day later Austria-Hungary

- declared war on Serbia. The Education and Legislation Committee also approved Lincoln’s requests.

After all the effort to get approval to return to Stanford, Lincoln informed Charles Adams, Secretary-Treasurer at the Law Society of Alberta, and the Benchers, in December of 1914, that he would not be returning to California. Instead, he would engage in studies at the University of Alberta.

After all the effort to get approval to return to Stanford, Lincoln informed Charles Adams, Secretary-Treasurer at the Law Society of Alberta, and the Benchers, in December of 1914, that he would not be returning to California. Instead, he would engage in studies at the University of Alberta.

Though much of Lincoln’s decision concerning law school had taken place as tensions in Europe were on the rise, it is unclear if the outbreak of hostilities had any affect on his choice to remain in Canada. Despite his age, it appeared he had not enlisted in active service by the end of 1914, and it was not clear if he intended to enlist.

Through January 1915, a number of letter exchanges between Lincoln and Charles Adams indicates some confusion over the former’s first-year examinations. Lincoln may have believed that he should be exempt from examinations because he had attended law school at Stanford. His letters are somewhat ambiguous when communicating his requests, which added to the confusion at the Law Society of Alberta. For example, despite numerous exchanges between Lincoln and Adams, the former doesn’t mention his intention to seek an exemption until January 22, 1915.

Adams responded to this request on January 23, 1915 stating, “it was not the committee’s intention to grant you the last part of your request, viz., that you be excused from taking the examination prescribed for first year students.”

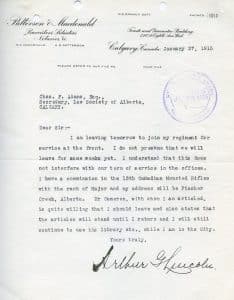

All this became immaterial on January 27, 1915, when Lincoln informed Adams by letter that he would be joining his regiment shortly for active duty in Europe. He was commissioned to the 13th Canadian Mounted Rifles in Pincher Creek, Alberta and given the rank of Major. Interestingly, while he remained in Canada he would continue to article with McKinley Cameron. He wrote, “Mr. Cameron, with whom I am articled, is quite willing that I should leave and also states that the articles will stand until I return and that I will still continue to use his library etc., while I am still in the city.”

In a follow up letter, Adams informed Lincoln that at the Benchers’ Convocation in January 1915, it was decided that certain exemptions would be given to students who left to fight oversees. The letter stated, “that any student who is at the time of any examination (except the final examination) upon which he would in ordinary course have written in order to have completed his three annual examinations within the term of his services, he is exempted from taking such examinations…” Lincoln was able to leave for Europe with the intention of continuing his studies unaffected upon his return.

student who is at the time of any examination (except the final examination) upon which he would in ordinary course have written in order to have completed his three annual examinations within the term of his services, he is exempted from taking such examinations…” Lincoln was able to leave for Europe with the intention of continuing his studies unaffected upon his return.

There is very little written detail about Lincoln’s military service oversees during World War I, other than a clipping in the Calgary Herald on September 20, 1930, announcing his death. Initially he served in the 13th Canadian Mounted Rifles. He transferred to the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, and then to the Royal Air Force. He finished the war with the British Flying Squadron and was stationed in Italy, England and France. He held the rank of Major with the Canadian Expeditionary Force, the Canadian Militia and the Royal Air Force. He was discharged on April 5, 1919, and was the recipient of the Mons medal.

Following his return to Alberta, Lincoln experienced a number of difficulties getting admitted to the bar. His exam grades were subpar. This is understandable as he had just spent four years in active service oversees. It does appear that initially the Law Society was unable, or unwilling, to grant the exams exemption. In a letter Lincoln wrote to the Law Society, he explained the special exemptions and provisions given by the Law Society of British Columbia for returning soldiers. Curiously, he did not mention the exemptions laid out by the Alberta Benchers at their January 1915 Convocation.

Making matters worse, Lincoln failed to declare what caused his absence. However, following the submission of a Statutory Declaration on August 5, 1919, Lincoln was granted exemptions for his first and second exams, and permitted to take a supplementary examination despite have scored low in his final exam in May 1919.

Despite completing his exams, Lincoln’s difficulties did not end. Having continued his articles with McKinley Cameron, he failed to declare this fact formally to the Law Society of Alberta. This information was required for admission to the Law Society of Alberta. In a letter dated September 22, 1919, Adams advised Lincoln that having not properly confirmed his articling arrangement might make it difficult to gain admission to the bar.

Despite completing his exams, Lincoln’s difficulties did not end. Having continued his articles with McKinley Cameron, he failed to declare this fact formally to the Law Society of Alberta. This information was required for admission to the Law Society of Alberta. In a letter dated September 22, 1919, Adams advised Lincoln that having not properly confirmed his articling arrangement might make it difficult to gain admission to the bar.

The complications continued when Lincoln filled out his admission forms incorrectly on November 1, 1919. This prompted a misunderstanding with regards to his status as a student-at-law. Lincoln also declared that he was a graduate of Stanford Law School. However, the Law Society had no record of him graduating from that school. While there is nothing in the records to show that these complications were resolved, Lincoln was admitted to the Alberta bar on November 27, 1919.

It is unclear whether Lincoln practiced law in Alberta beyond his articles. Immediately prior to his admission, Lincoln wrote a letter to Charles Adams on November 14, 1919, informing the Law Society that he would be moving to Ottawa to engage in government work and that he would not be commencing his law practice. He remained a non-practicing member until the end of 1920. As of January 1923, Lincoln relocated to Los Angeles, California.

While on a road trip to Quebec, Lincoln died in a Kansas City hotel on September 19, 1930. There is no record of practicing any law in Alberta between 1921 and his moving to the United States. There were a number of inquiries with respect to the whereabouts of Lincoln. The letters suggested that he did so some legal work, but this may have been during his articles. Adams could only reply with the last known address on record.

There were a number of returning Alberta lawyers who did not practice law for a number of reasons. Arthur Gardner Lincoln’s case was likely unique. Before and after the war, he took all the necessary steps to be admitted to the Law Society of Alberta. It certainly appeared he wanted to become a lawyer. However, it is unlikely that he ever practiced in Alberta, and the reasons remain as ambiguous as his admissions process.